The Parliament election in Norway, Europe’s largest oil and gas producer, ended up securing support for a shift in Government, from today’s Conservative-coalition government to a Labour-coalition government. Talks and negotiations are happening over the next weeks, and one of the biggest issues is the future of the Norwegian oil and gas industry. Will Norway’s new government pass a more restrictive oil and gas policy?

Despite Norway portraying itself as being a climate champion, they are one of the world’s largest exporters of fossil fuel emissions, exporting oil and gas equivalent to nearly 10 times Norway’s own domestic emissions every year. The last couple of years the debate over the country’s oil and gas production has increased in strength, and several parties have called for a ban on future licensing rounds, and a managed phase out of oil and gas production.

For the past 8 years the conservative Government has led an aggressive expansion and exploration policy for the oil and gas sector. The conservative Government has awarded 545 exploration licenses. This at a time when the science has never been clearer on the need for a rapid phase out of fossil fuel production.

In the election debate, the question on whether to continue to explore for more oil and gas and allow new field development has been one of the biggest issues. This debate intensified following the August report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the related call from UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres that the world must stop exploration and production of new oil and gas.

Some countries are beginning to heed this call, with Denmark and Costa Rica unveiling the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance this week, a new diplomatic initiative that will bring together countries that have ended licensing for new oil and gas exploration and production and are setting an end date for their production. Norway, as one of the world’s wealthiest oil and gas producing countries, has an urgent responsibility to lead in phasing out its own production.

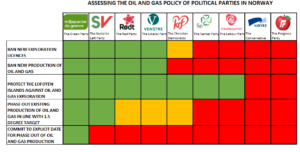

Several of the Norwegian parties are beginning to recognize this. Mapping done by OCI shows that four of the nine parties in Parliament want to ban new exploration and new production of oil and gas.

With the results from Monday’s election, we see that the four parties calling for a much more restrictive oil and gas policy increased their votes by 4.8%. The Conservative Party and the Progress Party, the two parties that have overseen oil and gas policy for the past eight years, and had the minister for oil and energy, will lose 15 seats in parliament compared to the 2017 election results. Just which parties will join the Government is so far unclear, as talks and negotiations between the Labour Party, the Center Party and the Socialist Left Party will happen over the next few weeks – until mid October.

Before the election, polls indicated that the Green Party, the Socialist Left Party, and the Red Party would win an even higher percentage of the votes than they ended up gaining. Ultimately, the progressive parties have gained an additional 11 seats in Parliament, whereas hopes were that they would gain 20-25 seats and be an even greater force to deal with. Nonetheless, the parties opposing new oil and gas in Norway have gained much momentum and strength this election.

The question now is which path a new Government will take on the oil and gas issue. There is no doubt that the Socialist Left Party will push for a much more restrictive oil policy, with a ban on new exploration. But, within the Center Party there are strong pro-oil forces. Their deputy leader Ola Borten Moe is the owner and one of the founders of the Norwegian oil company OKEA. He founded the company two years after he stepped down as Minister of Oil and Energy. And together with Labour and the Progress Party, the Center Party was part of the coalition in parliament that ended up passing a massive bailout package for the Norwegian oil and gas industry in 2020, with more than 7 billion NOK in subsidies.

Still, within the Labour Party there is a clear and growing climate wing that is pushing for the party to align its oil policy with the reality of the climate emergency. Spearheading this force is the Labour Youth Party, which led the opposition against oil exploration outside the Lofoten islands for several years. They won this fight at the Labour Party’s bi-annual conference in 2019 when it committed to protect the areas from oil exploration.

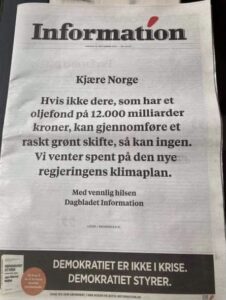

All of this means that the future for Norwegian oil and gas production is still undecided. Nonetheless, it looks near impossible for the industry to continue as is. In the past, shifting Governments have had one thing in common: they’ve let the country’s oil policy dictate its climate policy. The new Government declaration will need to mark a clear shift in Norwegian oil and gas policy, and start aligning it with the Paris Agreement. The day after the Norwegian election, this was pointed out by the Danish newspaper Information, which dedicated their front page to the new Government in Norway, and in their editorial, urged the new Government to ensure a transition away from fossil fuels.

If there are no changes in the Norwegian oil and gas policy, and Norway continues to explore for and develop new reserves, the country is forcing a more difficult transition on other countries (as well as itself). From science we know all too clearly that there is a finite global carbon budget, and each barrel of oil extracted in Norway is a barrel that cannot be extracted elsewhere. A managed decline away from fossil fuels will need to be undertaken by all nations around the world, and new fossil fuel development anywhere is incompatible with staying below 1.5C. But, the poorest countries will need significant support and more time to wind down their production and diversify economies. Justice and equity dictate that wealthy countries with the capacity to transition rapidly – such as Norway – move first and fastest.

A transition of the Norwegian economy won’t be easy, when the oil and gas industry accounts for 14 % of the country’s GDP and 14 % of the government revenue. Nonetheless, the Norwegian economy is more diverse than a lot of other major producers, and the country also has significantly more resources to ensure a fair and managed transition.

A 2020 report from Statistics Norway shows that the economic consequences of banning new exploration in Norway would be modest. It found that over the course of 30 years, ending new oil development would reduce Norway’s GDP growth by 0.5% compared to the baseline-scenario; the GDP as a whole would still rise. Unemployment would increase by a maximum of 6,500 people, which is 0.2 per cent of the labor force. The Government can and should put transition support policies in place that ensure no worker is left behind and guarantee secure jobs with equivalent or better pay.

This means that Norway has both the responsibility and ability to take the lead. If a new government delivers a more restrictive oil policy, in line with the 1.5°C target, Norway will raise the bar and potentially set a new standard for climate leadership among a major oil producer internationally. There is no country in the world better equipped for a just and managed phase out of fossil fuels.

Norway must act on the need to phase out fossil fuels. This starts with putting a stop to new exploration and new development of oil and gas on the Norwegian continental shelf