Many people are waiting with baited breath to see what kind of clear action on climate change will come from the White House.

Many people are waiting with baited breath to see what kind of clear action on climate change will come from the White House.

The tick list should start with stopping the Keystone XL pipeline and banning oil drilling in the Arctic.

Whether the President delivers on these measures remains to be seen. What we know is that they will be hotly contested. Other more subtle measures are apparently being considered. Brian Deese, the deputy director of the National Economic Council, said that corporate tax reform was likely to be central to efforts to drive clean tech investment.

“The way that corporate tax reform gets done could have a dramatic effect, long term, about the incentives for investment in the United States for different types of technologies, renewable technologies”. He added that the Obama administration wanted to see “a level playing field” for renewables.

As well as investing in clean technology and trying to tackle oil subsidies in order to create a level playing field for green technologies, maybe Obama should start thinking about the long term and how much oil and gas we can actually burn.

He should start by reading a new report from economists at HSBC which looks at how much “unburnable carbon” should be left in the ground. It would not only make uncomfortable reading for Obama, but also for the oil majors.

In many ways, the KXL decision is about “unburnable carbon”, because the pipeline will facilitate the burning of carbon from the dirty tar sands we cannot afford to burn. Arctic drilling is also carbon that comes at too high a price.

But there are wider risks to the energy sector that Obama should realise, understand and act on, because it has implications for American oil companies.

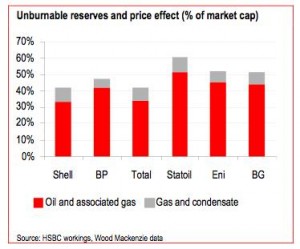

The report suggests that European oil majors, BP, Shell and Norway’s Statoil could lose some 40 and 60 per cent of their market value if the International Energy Agency’s “unburnable carbon” scenario was put in place.

HSBC argues that there is a real risk to the market capitalisation of these groups not just because much of their assets would have to be left in the ground, but also because the price of oil would fall as demand falls.

Firstly the direct costs and the numbers do not look pretty, especially if you are Bob Dudley the head of BP. It says up to 25 per cent of BP’s proven and probable reserves would be unburnable, equating to around 6 per cent of its market value. But BP is not as bad as Statoil’s unburnable carbon reserves, which amount to 17 per cent per cent of its market capitalization.

What the bankers argue is that the oil market is still failing to think about a low carbon future. “Because of its long-term nature, we doubt the market is pricing in the risk of a loss of value from this issue,” the report says.

The economists add: “We believe that investors have yet to price in such a risk, perhaps because it seems so long term. And we accept that our scenario probably exaggerates the risk as we assume a low-carbon world today rather than beyond 2020. However, we believe it does give an indication of the potential impact on the sector. “

It impacts the oil sector, but whether much of these reserves will be burnt lies with governments and not companies. Some 70 per cent of the world’s proven oil reserves are controlled by governments.

If Obama wanted to send a strong international signal, he could argue that the US now recognises that some carbon should remain unburnt. And that also includes reserves in the US as well as the dirty tar sands coming over the border from Canada.