Jump to Section:

- Why Campaigning on Subsidies and Public Finance for Coal is Key

- Targeting Subsidies and Finance to Stop a Coal Project

- Use Information on Subsidies and Finance to Slow Down the Project

- Ground Project-Based Subsidy and Finance Work in a Campaign at the Local Level

- Identify Subsidies and Finance Supporting a Coal Project

- Choose Which Subsidies and/or Financing to Target

- Strategies and Tactics

- Box 3: Indonesia: Targeting Subsidies and Public Finance in Project Campaigns

- Campaigning on National Subsidies to Coal

- Identify National Subsidies and Finance to Coal

- Choose Which Subsidies to Target

- Strategies and Tactics

- Box 4: Success on Exploration Subsidies in Australia

- International Campaigning for Subsidy Reform and Transparency

- Campaigning to End International Public Finance for Coal

- Political Momentum for International Subsidy Reform

- Transparency of Coal Subsidies and Finance

- Strategic Arguments against Coal Subsidies

- Coal Subsidies are Simply NOT the Best Use of Public Money

- Removing Coal Subsidies Doesn’t Have to Harm the Poor

- Coal Doesn’t Increase Energy Access for the Poor

- Renewables Create More Employment Opportunities than Coal

- Coal Creates Pollution, Harms Public Health, and Contributes to Water Scarcity

- Coal Undermines Climate Change Commitments

- Supplemental: Targeting International Public Finance

Why Campaigning on Subsidies and Public Finance for Coal is Key

At the local level, large-scale coal projects are most often backed by significant subsidies and in many cases public finance and/or guarantees directly make the project financially viable. Taking that support away can mean the difference between a coal project moving forward or being stopped. Taken collectively, the elimination of significant amounts of subsidies and public finance for coal at the national and international level can help shift investments towards clean energy.

A large majority of coal projects globally are financed by a web of public (subsidized) finance and private bank/investor contributions. Large-scale coal projects are associated with high investment costs, high risks (e.g., regulatory, social, and environmental), and take a relatively long time to build. In order for coal projects to be viable they need large amounts of long-term finance (10-15 year repayment periods) and insurance (e.g. government loan guarantees) to reduce the substantial costs and risks.

Such long-term finance and insurance is often not available from the commercial sector, especially in developing and transition economies. Public finance and other subsidies are often the key factors determining whether a coal project gets built or not. Public finance provides capital at lower interest and/or at longer tenor (repayment periods), making coal projects more affordable and giving them the ability to secure further finance. Even when commercial finance packages are available, they are still most often backed by public insurance/guarantees and other forms of subsidies.

A recent assessment on public assistance to coal in Indonesia found that the vast majority of the large-scale coal plants (600 MW and larger) built since 2006 were made possible through public finance and guarantees.

Adding the subsidies lens, i.e. the consideration of the use of public money, to any coal campaign adds to the available toolbox to fight a project, and it can also broaden the intervention opportunities and gain support from actors who previously were not concerned or did not understand their connection with coal development issues.

When national coal subsidies can be eliminated or when international finance institutions can be taken off the table for coal finance, the playing field for coal development begins to change. National subsidies often disproportionately favor conventional energy, and shifting public support away from fossil fuel technologies can be incredibly helpful for investments in increasingly cost competitive renewable energy options.

Public financing often supplies a ‘stamp of approval’ for financially and socially risky projects. The commitments from major multilateral development banks and several countries to stop international finance for coal projects except in limited circumstances begins to close doors to the coal industry more broadly. In the short term, the coal industry will look towards financing from institutions that have not committed to move away from coal, but if the number of governments and institutions saying no to coal spreads, this would create a real obstacle to future coal development.

Additionally, less public money for coal also means more public money is available for other uses – for instance, for clean energy solutions and other services.

Return to Top ⇧

Targeting Subsidies and Finance to Stop a Coal Project

Many anti-coal campaigns are at the individual power plant, mine, or rail project-level. This is often because the affected population and issues are more tangible than government-wide policies or actions resulting in subsidies. There are many existing resources and information to provide guidance on this front.

This section aims to provide guidance on enhancing project campaigns by adding the coal subsidies angle to those efforts. As discussed throughout this toolkit, public finance and other subsidies are key to the feasibility of a majority of large-scale coal projects.

Use Information on Subsidies and Finance to Slow Down the Project

- One of the key ways that subsidies and finance can be used to stop a project is to slow it down. Time is money, and the more wrenches thrown to disrupt and delay the project process the more chances the project will be stopped. Investors want their money to make more money. If investments are committed to a project that is not progressing, it is not making money and investors will seek to put their money somewhere else. Delaying the project’s financial closure can kill a project.[1]

- Challenging the subsidies supporting a project and thereby getting the public to demand more accountability can directly take away necessary capital and guarantees, or slow down public financing process the process to scare away investors. Threatening funding and slowing down financial closure are key tools to stopping projects.

Ground Project-Based Subsidy and Finance Work in a Campaign at the Local Level

- Before beginning subsidy work to target a project, make sure that the local issues around the project are clear and that relationships have been established with local communities. For instance, it is essential to establish a strong relationship with and a clear understanding of the needs and concerns of the project-affected communities. When possible, a campaign should build capacity of the project-affected community leaders to understand the role of public finance and other subsidies in the coal project. Even when national governments ignore and intimidate the communities, their voices are often listened to by the international actors and media.

- The first step to utilizing subsidies in a coal project campaign is to determine the source and amount of subsidies/public money supporting the project. The initial assessment can be approached in the same manner as the national government subsidy assessment, but at the project level (see Identifying Subsidies section). Coal Swarm may also have good resources on specific coal projects.

Identify Subsidies and Finance Supporting a Coal Project

Choose Which Subsidies and/or Financing to Target

- A particular subsidy may be key to making a project financially viable. If a subsidy that has been identified seems particularly large or important, it may be a good point of intervention. This could be public money, guarantees, low cost land, or tax breaks.

- A particular subsidy may be scandalous or have caused problems in the past. If a certain type of subsidy is particularly contentious or has made news in the past, a new project or recipient could present a good opportunity to fight against it.

- Financing may not yet be approved. It is much easier to stop finance from a public institution before it is approved. If you have found out that a national fund, a development bank, or a bilateral agency is considering but has not yet approved a certain project, this can make it a stronger target.

- Financing may be from an institution with strong safeguards or finance criteria. When particular banks, such as the World Bank, are involved in a project, even indirectly, it may be possible to trigger social and environmental reviews when the project is particularly contentious. Other MDBs and bilateral agencies also have social and environmental guidelines that may trigger a project review.

Strategies and Tactics

- Identify who has the power to affect the subsidy or financing. The power to change the subsidy or financing supporting a project is different depending on the support in question. Identify which government officials, international governments, or institutions are able to influence the target subsidy.

- Identify what can be done to slow down the financing. Getting a public institution to cancel or not approve its support for a coal project can undermine and disrupt a project’s finance package.

- Working for a ‘no’ on MDB financing: If multilateral banks are involved, work with groups internationally to raise awareness of project problems in the lead up to any board votes on project finance. All projects, operational policies, and country and sector strategies at the MDBs need to obtain executive board approval. Thus, it is important to campaign well in advance of Board approval dates as it is easier to change or stop a policy or project before it gets approved. For upcoming World Bank projects under preparation, check the Bank’s Monthly Operational Summary. At the very least, work to ensure that the US, UK, Netherlands, and the Nordic countries vote “no” on the project (i.e., not simply abstain) and encourage other governments to do the same.

- Pressuring international governments to decline or withdraw bilateral funding: If bilateral finance is involved or being considered, work with groups internationally to pressure those institutions not to fund the project or to withdraw funding.

- Triggering international safeguards: Often when international finance is involved, the project must be in compliance with social and environmental safeguards/performance standards of the institution financing the project. If these safeguards are not met, the finance institution can be asked to review the project or to suspend finance. By requiring the project to provide evidence of compliance with IFI policies, the project process can be slowed down, sometimes pushing back deadlines on land acquisition, environmental permits, and other key steps which can push back financial closure and possibly result in investors pulling out of the project.

- Pressuring national government finance through international institutions. Sometimes, international institutions – particularly the World Bank and ADB – have a role in setting up national funds that back coal projects, particularly in emerging economies and developing countries. If this is the case, the national institution may have de facto international standards that can be used as described above. See Box 3 on the Central Java Power Plant.

- Demand accountability. All of the MDBs have accountability and/or grievance mechanisms, such as the World Bank’s Inspection Panel, that are charged with ensuring the institution’s compliance with its operational policies and social and environmental performance standards and safeguards. Project-affected citizens can file complaints with these mechanisms, which in some cases have proven useful to delay or improve projects and offer a cheap alternative to expensive court cases. Many CSOs have experience filing such complaints. See the cases involving the Tata Mundra coal power plant in India and the Eskom Medupi coal power plant in South Africa.

- Raising awareness to increase public pressure: Consider how to best expose the use of public money for the project. Exposing the public funding can help gain more public support to oppose the project from actors who previously did not feel a connection or concern.

- Pick appropriate arguments for the audience. Depending on the subsidy or financing targeted, and who the decision makers are, different arguments may be useful. National level officials may be concerned with:

- Money going to the project conflicting with support for other initiatives

- Project objectives not being met

- How the money could be used effectively in other ways

The international finance community may be sensitive to arguments like:

- Social and environmental concerns around the project

- The climate impact of the project in light of institutional or global climate goals

- The project will not satisfy their stated mission and various pledges on sustainable development, poverty reduction, and energy access

Also see section on Strategic Arguments against Coal Subsidies.

Return to Top ⇧

Box 3: Indonesia: Targeting Subsidies and Public Finance in Project Campaigns

Central Java Coal Power Plant – Indonesian groups, including Greenpeace SE Asia, Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation, and local communities, are campaigning against the Central Java Coal Power Project (a 2,000 MW plant). The local campaign has focused on many issues including, inter alia, the government of Indonesia’s (GOI) non-compliance with environmental impact assessments, the project’s exemption from a protected marine area, lack of consideration for fishermen and farm laborers, and intimidation involved in the land acquisition process. A further strategic angle and international attention have been gained by exploring the public finance and subsidies involved in the project. As it turns out, the World Bank, ADB, and JBIC are all participating in the project.

Through policy lending, the World Bank and ADB supported a list of investment incentives and tax breaks, for the new public-private partnership (PPP) power plant. In addition, through a financial intermediary (FI) – the Indonesian Infrastructure Guarantee Fund – a government guarantee was provided to the Central Java project. Local resistance and campaign efforts so far have succeeded in pushing back the financial close deadline for two consecutive years. In addition, international campaigns targeted at the World Bank and JBIC have also helped to slow down the project by demanding investigations into the project’s compliance with World Bank and JBIC social and environmental safeguard policies. Moreover, the Central Java Coal Power Plant has put a spotlight on how policy lending and FIs can promote coal development. World Bank campaigners are using this case to demand stringent safeguard policies for the World Bank’s policy lending operations, which are currently significantly weaker than safeguards for project lending.

Coal Mining Licenses – Indonesian groups, including WALHI, are demanding that the South Sumatra Government revoke the licenses of 31 coal mining companies due to unpaid taxes. These 31 companies do not have a tax identity number and thus, have not paid taxes amounting to an estimated US$9 billion over the past three years. WALHI further points out that many of these and other mining permits are in conflict with protected and conservation forest areas – representing exemptions to land use control policy – a further issue that needs to be rectified whether or not the company has paid taxes.

For other examples of targeting public finance to stop coal projects, please see: IFIs pull out of Turkish coal project – NGO pressure integral and Bangladesh, Phulbari Coal Project.

Return to Top ⇧

Campaigning on National-Level Subsidies to Coal

National and sub-national governments offer a range of incentives and public financing measures to support investment in the coal industry. Other countries or multilateral institutions may also offer incentives for coal production within a country. These measures can broadly support the industry, drive expansion, and can also make the economics for specific projects viable. Working to change a subsidy policy that affects the coal sector across the board can be extremely helpful to coal campaigning in the long term because it means that far fewer coal projects will be proposed to begin with.

Identify National Subsidies and Finance to Coal

- The first step to targeting national subsidies to coal or international finance coming to coal in a particular country is to determine the source and amount of subsidies and public money supporting coal. There’s a country-level assessment for Indonesia, and soon to be more, that has been completed. Or, use the information in the Identifying Subsidies section of this report to determine national level subsidies.

Choose Which Subsidies to Target

- There are a number of factors to consider in determining which national subsidies or finance to target for a campaign effort. Although opportunities will vary by country, and the best points of intervention will depend on the political situation, the following considerations will be useful for any country context:

- Are the subsidies among the largest in the country, either by value, amount of finance they leverage, or support for key infrastructure requirements? For instance, particular publicly subsidized loans and guarantees may turn out to be the key financing components for proposed power plants. Increased coal production may be driven by low royalty rates, tax incentives, and/or underpriced exports. Subsidized rail and ports may represent key infrastructure requirements for increasing exports. A particular international institution or bilateral agency may be providing significant assistance to a number of projects in the country.

- What subsidies are driving the most industry expansion? Determine whether any subsidies support the expansion of the coal industry, either through increased production, mining, or exports, exploration incentives, or building and expanding coal power plants. Government plans for industry expansion are typically made public in country economic development strategies or sector-wide strategies for power, mining, and infrastructure, and subsidies often exist or are created to support these plans. MDB country strategy documents are also a good source of information on future development plans. Important government initiatives and supporting policies to watch for include:

- Development strategies/investment plans (power, mining, infrastructure)

- New Regulations, including privatization, public-private partnerships (PPP)

- Taxation and royalty rates

- Contract and concession schemes – terms can supersede statutory laws

- Investment incentives

- Land acquisition process

- New governmental agencies or funds with powers to grant exemptions and benefits

- What are the most egregious and socially unpalatable subsidies? Consider if any subsidies are particularly outrageous and related to issues that would cause public outcry, such as large amounts of illegal, i.e. untaxed, exports due to corruption or lax government oversight; lower royalty rates or electricity tariffs for large companies; or any exploration subsidies, which conflict with the carbon budget.

- Is coal support coming from MDBs or bilateral finance that has coal lending restrictions or strong social and environmental policies? In addition to projects, international finance may be supporting the country’s coal development plans through policy lending, technical assistance, advisory services, or direct project investments. If international finance is involved, there may be additional leverage to affect that support, as international involvement can broaden the scope and increase international support for the campaign.

- What are the most likely subsidy (subsidies) to be eliminated? Choose subsidies that are less politically challenging, which will likely be producer subsidies instead of consumer subsidies. If consumer subsidies are targeted, it will be important to assess impacts on the poor and provide safety net measures and tariff structures that protect the poor’s access to affordable electricity and fuel.

Strategies and Tactics

- Identify those with the power to change the subsidy. In building a campaign to eliminate coal subsidies, it is essential to identify the groups or individuals who have the power to eliminate the subsidy, including the government ministry or agency that is responsible for the targeted subsidy (e.g., Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Mines/Energy, SOEs, etc.); important political actors who could become political champions of the cause (parliamentarians, governors, or mayors); and outside actors that have influence on the government and sometimes are the decision-makers on certain policies, e.g. International Monetary Fund (IMF).[2] Note however that the use of outside actors can be tricky or inappropriate depending on the institutions and the country context.

- Identify individuals or groups who can influence the decision makers. Decision-makers are influenced by public pressure and the media, which means the campaign needs to focus on messaging and arguments that speak to this audience and moves them to take action. Sometimes outside actors such as foreign governments (e.g. larger donor countries or regional trading partners), international institutions (e.g. United Nations), or a coalition of local and international CSOs can be a big influence on decision-makers. Sometimes it may be useful to have influential or respected individuals carry a message. It should be kept in mind that who delivers the message can be just as important as what the message says.

- Identify opportunities for activities or media pushes. In order to get the most media and public attention to the campaign or have the best chance of affecting policies, public activities (e.g., protests, petitions) and report releases should be timed to take place ahead of or during strategic events, such as:

- Awarding of new contracts or concessions (offer a counter to industry demands)

- National and local elections

- Voting on or proposing of new regulations

- Announcement of or consultation on development strategies

- Industrial accidents or scandals

- G-20, APEC, UNFCCC meetings (highlighting international commitments)

- Pick appropriate arguments against the subsidies. It is important to increase the public understanding of subsidies supporting the coal industry and who it benefits. As part of this understanding, it is important to communicate the public costs of coal subsidies and the benefits to getting rid of them, such as better and cleaner energy alternatives and increased government budget for social spending. Just as the specific subsidies to be targeted depend on the country context so will the arguments selected to combat them. In some countries the strongest argument against public assistance to coal might be climate change. For other countries, it may be more important to emphasize cleaner energy alternatives for the poor. Strong arguments can be made on several fronts including:

Return to Top ⇧

Box 4: Success on Exploration Subsidies in Australia

The Paid to Pollute campaign represents a coalition of over 20 civil society organizations in Australia campaigning to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies. In 2013, the campaign scored an important victory by getting mining exploration deductions removed from the federal budget, which will save $1.1 billion over four years. Paid to Pollute provides great examples of many tactics important to campaigning on subsidies:

Best use of public money – By identifying and quantifying the exploration subsidy, the campaign effectively used the figure of $1.1 billion in taxpayers’ money for exploration deductions to catch the attention of the public and government actors. In addition, the campaign used the victory on this subsidy to highlight the missed opportunity to eliminate the government’s huge fuel tax credit (which is also significant to mining) pointing out that it cost AU$5.9 billion in 2013-14, which is half of the government’s total spending on schools. The campaign continues to make the point that such subsidies come at the “expense of nation building projects that are still lacking funds.”

Public pressure – The campaign highlights the fact that cutting the mining subsidies are supported by the public. As evidence, the campaign uses polling conducted for Market Forces in January 2013 showing 64% of Australians were opposed to the mining industry’s fuel tax credits, with the highest opposition (72%) found in Queensland, the largest coal exporting state in Australia.

Climate change and pollution – The point of the environmental impacts of these subsidies is clearly made starting with the very clever name of the campaign – Paid to Pollute. In addition, the campaign points out that despite the progress brought by the decision to reduce the exploration subsidy, there still exist four major fossil fuel subsidies that the government must cut in order “to consolidate Australia’s transition to a low carbon economy and protect taxpayers’ funds by ending wasteful and polluting fossil fuel subsidies.”

Strategic timing and international commitments – The Paid to Pollute alliance has vowed to continue campaigning against fossil fuel subsidies in the lead up to the 2014 G20 meeting, which Australia will host. As Chair, Australia may find it difficult to justify providing among the highest levels of producer subsidies of the G20 nations, given that the group has collectively pledged to phase out fossil fuel subsidies.

Return to Top ⇧

International Campaigning for Subsidy Reform and Transparency

Campaigning to End International Public Finance for Coal

International public finance – through multilateral development banks (MDBs) and bilateral finance – provide incentives for coal through direct financial assistance, policy support, and other means. These institutions offer an interesting target for campaigning not only on the project level, but also on the policy level, because there is already significant public pressure and scrutiny on them.

There have been, and continue to be, campaigns on international financial institutions targeting the overall policies and portfolios of an institution or government.

Campaigning on the policies and portfolios of institutions. In 2013, the World Bank Group, EBRD, and EIB adopted policies or positions that heavily restricted their assistance to coal power plants. In addition, the US, UK, Nordic countries and the Netherlands also pledged to restrict their assistance to coal plants abroad. These coal-restricting policies were largely a result of CSO campaigns that exposed the level of fossil fuel funding of the MDB and bilateral portfolios.

Additional campaigning will be necessary to get the remaining coal-financing institutions and countries to make commitments. For the MDBs, these include ADB, IDB, and AfDB. For bilateral finance, these mainly include Japan (JBIC and NEXI), Korea (K-sure and Korea Export-Import Bank), Germany (Hermes and KfW), China (Chexim, CDB, ICBC, Bank of China), and Russia (VEB).

A powerful tool to use in international finance campaigns is to build on the momentum of the institutions and governments that have already announced coal restricting policies. In other campaigns on social and environmental issues, an effective strategy has been to shame any institution with weaker standards to match or do better than the institution with the highest standard.

There are a number of international campaign efforts moving to support additional commitments:

- In Japan, there is an on-going JBIC coal campaign “No Coal! Go Green! No to JBIC’s coal financing!” led by JACSES, Kiko Network, and FOE Japan targeting Central Java Coal Power Plant in Indonesia.

- Using international pressure to target NEXI and JBIC, Oil Change International and the Sierra Club joined forces with JACSES, Kiko Network, and FOE Japan to send an open letter to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe signed by over 30 groups ahead of his meeting with U.S. President Barack Obama in April 2014. The letter urged Japan to follow the United States and other countries’ pledges to stop financing coal overseas. As a result of related meetings with US government staff, President Obama raised concerns with both the Japanese Prime Minister and South Korean President about their financing of coal-fired plants abroad.

- Some members of ECA-Watch are spearheading work to encourage OECD members to adopt coal restrictions similar to the country pledges above for all export credit agencies.

Additionally, even though some the international institutions and governments have coal-limiting policies, the campaigning on these actors is not complete. For one, all of their policies provide for exemptions to the rule and only cover power plants, not mining or associated infrastructure. On the power plant front, it will be essential to watch for what will pass as “rare circumstances” in which coal power financing is allowed, and other loopholes unique to each particular institution or country.

Current international campaigning to limit “rare circumstances” and loopholes in commitments to limit coal financing include the following:

- The World Bank and EBRD are considering assistance for a 600 MW coal plant in Kosovo. A coalition of local and international CSOs is campaigning to show the enormous negative impacts of the plant and that Kosovo is a country with cleaner alternatives to new coal.

- US NGOs are watch-dogging the “rare circumstances” and non-power plant coal projects exception, particularly at the US ExIm bank, which has historically been a heavy funder of coal projects of all sorts.

- UK groups are trying to close the important loophole that the UK pledge to limit coal financing seems to not officially apply to the UK’s export credit agency – the country’s largest supplier of international coal finance.

In addition to assessing the “rare circumstances,” the MDBs in particular may continue to support coal developments through policy lending and advisory services. On this front, the World Bank (including the IFC) and the ADB are key targets due to the recent policy lending and technical assistance programs in coal-important countries like Indonesia, India, and Mozambique. It is also important to note that the policy lending is not always directly labeled as a coal, energy sector, or even infrastructure program support. Other MDB policy processes that often involve subsidies to the coal industry are privatization and public-private partnership (PPP) schemes.

Lastly, an important area that needs much more attention and investigation is the assistance to coal through financial intermediaries (see MDB section above). All the MDBs are involved in FI operations, but the World Bank and IFC are leading the pack and make for a good FI starting point. In addition to FIs in individual countries, the IFC is managing global FIs such as the IFC Global Infrastructure Fund (currently stands at $2.1 billion, with the ability to leverage much more) and the World Bank is planning to launch a Global Infrastructure Facility. Such FIs represent substantial under-scrutinized and unrestricted pathways for coal finance as the sub-projects receiving finance through these funds are not publicly disclosed.

Campaign efforts are underway to pressure MDBs to strengthen and fully enforce fossil fuel financing limits:

- NGOs are advocating for changes in the way that development policy loans at the World Bank are evaluated in order to catch instances when the policy loans support projects and development with significant environmental and social impacts. As a result of an Oil Change International assessment of the Bank’s policy operations in Indonesia, the US government has requested the Bank to assess and report back on concerns surrounding the Central Java Power Plant and other coal projects pending Indonesian government guarantees.

- NGOs are also working to get greater transparency on FIs so that this financing may be adequately evaluated for whether it includes coal. US NGOs have put the US government on alert to watch for coal assistance through FIs. As a result, the US voted in December 2013 against an IFC proposed $100 million equity investment in Saudi Arabian corporation ACWA Power International over concerns that it had greenfield coal projects in its portfolio.

- Oil Change International and CEE Bankwatch continue to monitor, assess, and expose the portfolios of MDBs on an annual basis.

For more information on how to target international public finance, go to CEE Bankwatch Network’s Kings of Coal online toolkit and the Bank Information Center’s website.

Political Momentum for International Subsidy Reform

G20 and APEC. On the fossil fuel subsidy front, there continues to be political momentum for reform at the national level, although it is complicated and slow and is generally focused on a subset of subsidies.

In September 2009, the leaders of the Group of Twenty (G20) countries committed to phase out “inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies” over the medium term to improve energy efficiency and security, boost investment in clean energy sources, and address climate change. This commitment was echoed by the leaders of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in November 2009, which added 11 new countries to the group committing to the phase-out. To date, 134 nations have declared their support for fossil fuel subsidy removal in at least one international forum. Other international fossil fuel subsidy reform initiatives include Friends of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform – a group of countries encouraging the removal of fossil fuel subsidies – and the proposed Secure Sustainable Energy goal of the United Nation’s Post-2015 Development Agenda.[3]

In spite of these high-level commitments, and proposals to phase-out fossil fuel subsidies, by and large, subsidies are not being eliminated by the G20 countries. Instead, G20 countries are changing their definitions of subsidies in order to avoid taking action.

Encouragingly, by 2018, the European Union requires that countries phase out coal mining subsidies. However, countries like Germany, Poland, and Spain have continued to provide large amounts of coal mining subsidies prior to the phase out.

Transparency of Coal Subsidies and Finance

The lack of clarity on how much public money governments provide in coal subsidies is a serious barrier to campaigning against and ultimately eliminating subsidies. Efforts to independently research coal subsidies and campaigning in country should be seen as an important first step to achieving transparency and reform on a larger scale.

As discussed in a June 2012 report by Oil Change International, reviewing the G20’s fossil fuel subsidy phase out pledge, the lack of transparency on subsidies continues to plague reform efforts. Following the G20 pledge to reform inefficient subsidies, the report found that G20 nations are changing their definitions, not their subsidy policies, and that self-reporting of subsidies is failing.

There are some public sources of data on national-level subsidies, such as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s fossil fuel subsidies data, but this resource has data on only 40 countries, and the data scope is limited. Additionally, the IEA’s coal data for 39 countries provides consumption, export, import, prices, and CO2 emissions estimates, which can be helpful in identifying subsidies in those countries. However, these sources miss many countries and only supply certain types of data and subsidies, often leaving out items that are not disclosed in government budgets, subsidies through state-owned enterprises, and international public finance.

In terms of international finance for coal, there is some public data available on multilateral development bank and bilateral finance institutions’ websites, although it is not always easy to locate. Additionally, this information is likely incomplete, as multilateral development banks often ‘hide’ support for coal in support for financial intermediaries, policy loans, and technical services, while many countries’ bilateral financing is not easily accessible and must be pieced together from disparate sources.

Oil Change International is collecting data on national subsidies and international finance for fossil fuels on its Shift the Subsidies website. Data on major multilateral development bank finance and the OECD data on national subsidies are already included in the site. There are plans to add data on bilateral finance and also go into greater depth on national subsidies in G20 countries, with a particular focus on identifying coal subsidies in Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey.

However, even with these substantial efforts to collect additional data, there is still much that is not public knowledge. With this lack of transparency, additional efforts to find and expose subsidies are very important to supporting reform.

Ultimately, individual governments will need to agree to tackle transparency of fossil fuel subsidies as an issue. Increased pressure from campaigning groups to own up to the amount of money being handed over to support the coal industry could contribute significantly to these efforts.

Existing resources on subsidy transparency include Access Info Europe and the Centre for Law and Democracy, experts in the right to access public information.

Return to Top ⇧

Strategic Arguments against Coal Subsidies

Building the argument for the elimination of coal subsidies can be made on several fronts, including climate change mitigation, improving public health, reducing public expenditures or compliance with international agreements. The arguments used depend on the individual country circumstances, timing and opportunities for change. The following section provides ideas for arguments and strategic messaging on issues surrounding public finance and subsidies to coal.

Coal Subsidies are Simply NOT the Best Use of Public Money

Coal subsidies support activities that:

- Generally don’t increase energy access for the poor

- Perpetuate economic injustice

- Create fewer jobs than renewable sources of energy

- Degrade the environment and use up land and water resources

- Cause climate change

Is this how taxpayers want their money spent? Probably not.

This argument is perhaps the most versatile argument against subsidies, as there are always alternative ways to spend money, and any argument against coal can be used in this situation, depending on the audience.

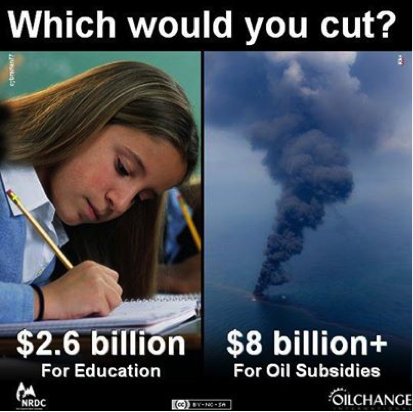

One way to highlight this is to contrast the amount of public money going towards coal and fossil fuels with the amount of public funds going towards social spending, clean energy development, or other areas important to the public. Easily understood and shared images can really help make the case about what public money is being used for.

Oil Change International (OCI) and Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) used the following images on oil subsidies in the United States to gain support for cutting oil subsidies when decisions were being made about what government programs to cut.

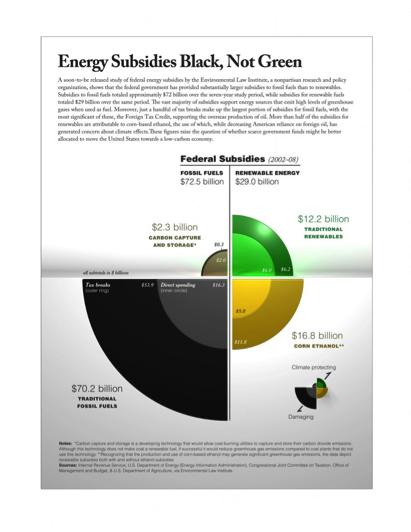

Environmental Law Institute made the following graphic showing the amount of fossil fuel subsidies versus the amount of clean energy subsidies in the United States:

Internationally, Oil Change and Global Campaign for Climate Action have highlighted the amount of money going to fossil fuel subsidies compared to climate finance from the world’s major economies:

Briefings and reports highlighting the disparity between dirty and clean subsidies can also be helpful, particularly for media and policy audiences. For instance, Oil Change has written briefings providing the World Bank Group’s energy lending statistics, emphasizing the Bank’s continued significant support for fossil fuels.

Removing Coal Subsidies Doesn’t Have to Harm the Poor

There is a great misperception that fossil fuel subsidy removal will necessarily harm the poor or that coal is the best way to provide energy access for the poor. It is important to communicate the reality that subsidies benefit the rich and powerful most. Furthermore, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), energy subsidies tend to be an extremely inefficient way to help the poor — most of their benefits go to the top one-fifth of the population. It is typical for the poorest 20% of households to receive less than 7% of the benefits generated by fossil fuel subsidies.

Furthermore, coal subsidies undermine the development chances of some of the poorest people in the world through public health and climate change impacts. Climate change is anticipated to negatively affect developing countries and the poor disproportionately – threatening recent gains in poverty reduction. Poor countries are particularly affected by climate change as they rely heavily on climate-sensitive sectors, such as agriculture and forestry, and their lack of resources, infrastructure, and health systems leaves them at greater risk to adverse impacts.

When consumer subsidies are targeted for removal, it will be important to assess impacts on the poor and provide safety net measures and tariff structures that protect the poor’s access/affordability of electricity and fuel.

Coal Doesn’t Increase Energy Access for the Poor

One of the main arguments used to continue public support for coal is that it is a cheap way to increase access to energy, but the reality is that coal power rarely goes to increase energy access for the poor.

Worldwide, it is critical for some 1.5 billion poor people to receive access to energy services in order to help pull themselves out of poverty. However, in most cases, large-scale coal power plants are not the most effective way to provide energy access to the poor. According to the IEA, more than 95% people without access to modern energy services are either in sub-Saharan Africa or developing Asia, and 84% are in rural areas. Given that the vast majority of those without electricity live in rural communities, small-scale, renewable energy is one of the best ways to help achieve energy access. Solar panels, wind turbines, and mini-hydropower all work well in rural areas where there’s no electricity grid.

When clearly substantiated, this argument can be effective for the media, government officials, and the development community. The following reports highlight how fossil fuels do not support energy access:

- Energy Access for the Poor: The Clean Energy Option. Oil Change International, ActionAid International, and Vasudha Foundation (India), June 2011. This report finds that only 9% of World Bank Group energy sector lending in 2009 and 2010 actually went to support basic energy needs in communities that lacked access to energy. The report also demonstrates that in India decentralized renewable energy systems are less expensive than extending the grid from a coal fired power plant to deliver electricity to the rural poor.

- World Bank Group Energy Financing: Energy for the Poor?, Oil Change International, October 2010. This study finds that none of the World Bank Group’s fossil fuel finance in 2009 and 2010 directly targeted the poor nor did it ensure that energy benefits are reaching the poor.

Renewables Create More Employment Opportunities than Coal

Another argument to continue public assistance for coal mining and power plants is employment creation.

Decisions-makers and the public need to be made aware that renewable energy provides more and safer employment opportunities than the coal industry. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), renewable energy employment stands at about 5.7 million presently (excluding traditional unsustainable biomass in developing countries and large hydropower), and may grow to well above 15 million by 2030 with appropriate policies. Coal, which has about four times more energy share, presently provides 7 million jobs worldwide.

In addition, IRENA estimates that reaching the objective of universal access to modern energy services by 2030 could create 4.5 million jobs in the off-grid renewables-based electricity sector alone.

Coal Creates Pollution, Harms Public Health, and Contributes to Water Scarcity

Most coal campaigns already include arguments regarding the pollution, environmental damage, and negative public health impacts of coal. As discussed above, these are all negative externalities that should be included in the assessment of coal subsides for policies and projects. Although many coal campaigns already include these impacts, they often do not assign monetary values to the impacts, which is key for exposing the public subsidies associated with coal.

For the cost of public health impacts from coal, estimates in the US range from $100 billion each year in a 2010 National Academy of Sciences report to $345 billion each year in a 2011 Harvard Medical School study.

Greenpeace International has experience modeling health impacts for individual coal projects and assigning monetary values to those impacts. For example, see “The True Cost of Coal” report for China.

Another key cost that is receiving more and more attention and needs to be further highlighted and monetized is coal’s use of water resources, which falls under the subsidy category of government provision of resources at below market rates. The entire chain of coal based electricity production –coal mining, transport, power plant combustion, and ash disposal – has huge impacts on water. In addition to accounting for the potential price gaps in coal’s payment for water and the market value, the level of subsidization needs to include the costs of reduced water availability for drinking, household use, and agriculture/food production. For more on coal’s water impacts, please see Shripad’s Blog on the “Limitations of the World Bank’s Thirsty Energy”.

Coal Undermines Climate Change Commitments

Coal is the single greatest source of worldwide carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions accounting for 43% of total global CO2 emissions. While coal’s contribution to climate change may be a difficult argument for convincing some audiences, the impact of coal development on the climate is significant. In some situations, this argument may be quite effective, particularly for countries and institutions that are vocal about the impacts of climate change and their climate commitments.

Coal subsidies lead to excess production, demand, and use of fuels, which result in greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, they “tilt the playing field” against emerging renewable energy technology, making it more difficult to transition to cleaner energy sources and thus, a low-carbon economy.

The reduction of fossil fuel subsidies has always been understood to play a significant role in obtaining the goals of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Kyoto Protocol calls for Annex I Parties to “implement … measures … such as … progressive reduction or phasing out of market imperfections, fiscal incentives, tax and duty exemptions and subsidies in all greenhouse gas emitting sectors that run counter to the objective of the Convention”.

Furthermore, the International Energy Agency (IEA) pinpoints phasing out fossil fuel subsidies as one of four policies to keep the world on course for the 2-degree global warming target, at no net economic cost. The IEA has estimated that even a partial subsidy phase-out by 2020 would reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 360 million tonnes, which equates to 12% of the reduction in GHGs needed to hold temperature rise to 2 degrees. As such, during the Warsaw 2013 UNFCCC COP, 27 leading climate and energy scientists from 15 countries issued a joint statement that: “There is no room in the remaining carbon budget for building new unabated coal power plants, even highly efficient ones, given their long lifetimes.”

In some circumstances, campaign arguments to eliminate coal subsidies can be tied to government commitments on GHG emission reductions. To begin, given that scientists have determined that at least two-thirds of the world’s current coal reserves must not be burned if we are to avoid raising global temperatures above 2 degrees, then all governments should be called upon to immediately eliminate any subsidy for coal exploration to prevent the worst impacts of climate change.

Interested in targeting international public finance? Read more here.

Return to Top ⇧

[1] Financial closure for greenfield/new projects is defined as a signed, legally binding commitment of equity holders or debt financiers to provide funding for the project. This funding would account for a majority of the project costs, thereby securing construction of the facility. Financial closure is dependent upon acquiring the necessary permits, insurance/guarantees and project assets, such as land.For greenfield projects and concessions, financial closure is defined as the existence of a legally binding commitment of equity holders or debt financiers to provide or mobilize funding for the project. The funding must account for a significant part of the project cost, securing the construction of the facility. For greenfield projects and concessions, financial closure is defined as the existence of a legally binding commitment of equity holders or debt financiers to provide or mobilize funding for the project. The funding must account for a significant part of the project cost, securing the construction of the facility.

[2] The IMF does not support fossil fuel subsidies, see IMF, 2013. Energy Subsidy Reform: Lessons and Implications.

[3] Friends of FFS Reform – a group of eight countries (including Denmark, Finland and Sweden) that came together to encourage the transparent rationalisation and phase-out of inefficient (consumption and production) subsidies; and the proposed Secure Sustainable Energy goal of the United Nations’ Post-2015 Development Agenda includes a commitment to ‘phase-out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption.’