While record-breaking numbers of fossil fuel lobbyists swarmed around COP27 in Sharm-El-Sheikh, and countries dithered about including the words ‘fossil fuels’ in the COP decision text, delegates at a civil society side event heard more straight talk in one hour than they heard so far at the conference.

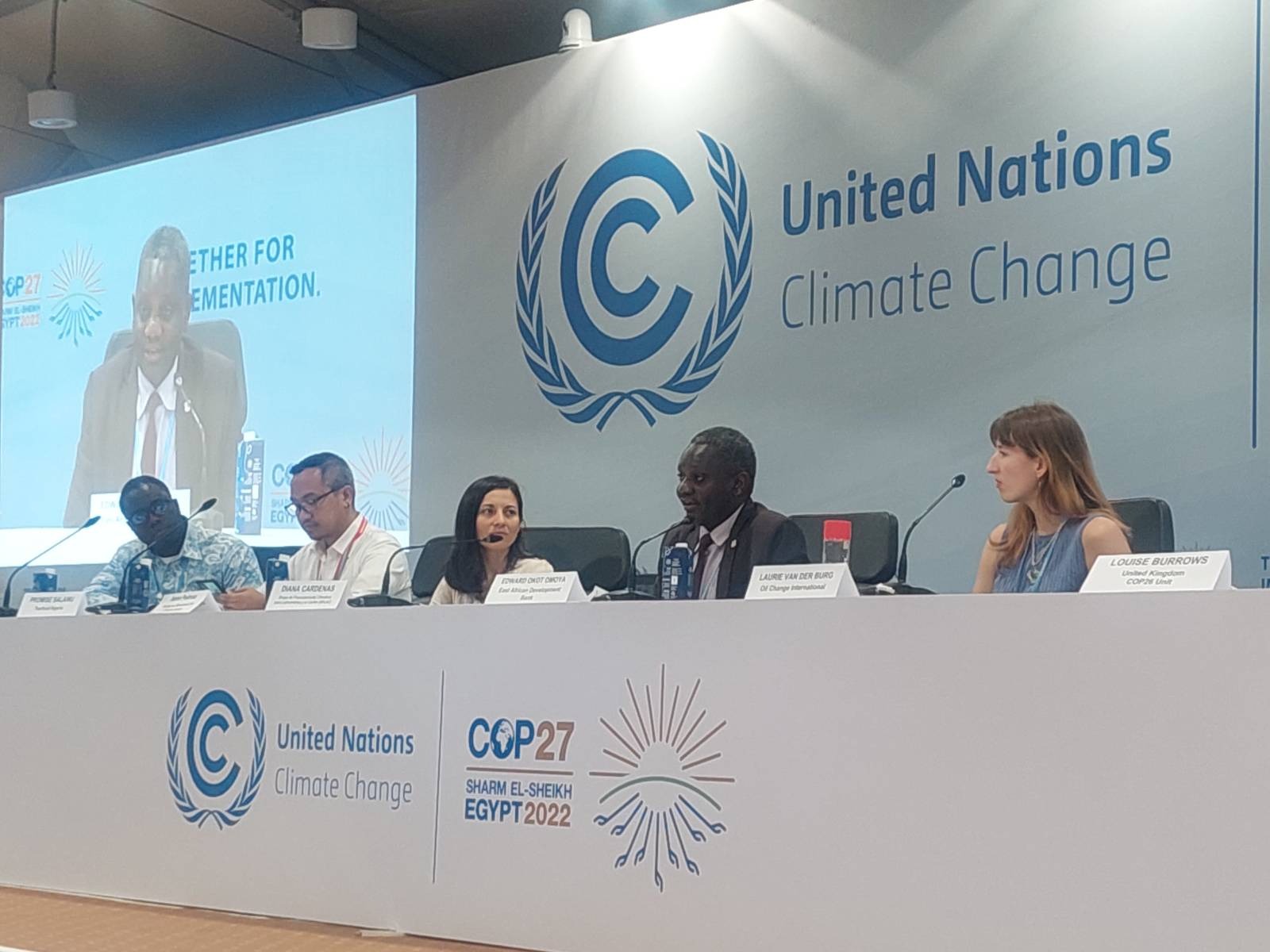

Oil Change International (OCI), Tearfund, Recourse, the Asian People’s Movement on Debt & Development and the Climate Finance Group for Latin America and the Caribbean (GFLAC) hosted a side event on Wednesday 16th November. It examined progress on the Glasgow Statement pledge for governments to stop funding international fossil fuel projects using public finance.

At the UN COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, 39 countries and institutions, including many EU nations, the United States and Canada, pledged to end international public finance for fossil fuels – with limited exemptions – by the end of 2022. It was one of the most concrete outcomes of the Glasgow summit.

With just a month to go, will these pledges be fulfilled?

Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate opened the event with a blistering speech that left panelists visibly emotional, detailing the pain and suffering caused in the Global South by the North’s fossil fuel addiction.

Ugandan climate activist @vanessa_vash speaking on the Glasgow #StopFundingFossilFuel pledge at the side event we co-hosted at #COP27 this afternoon. pic.twitter.com/nwoKXb4Bev

— Tearfund (@Tearfund) November 16, 2022

Nakate singled out Canada, the United States, Germany, and Italy in particular for backsliding on their Glasgow promise to stop funding fossils. “This outrages me,” she told attendees.

In the run-up to the conference, Canada, Germany and Italy have shown signs of reneging on their Glasgow Statement commitment. The United States has an ‘interim policy’ but has refused to make it public. The leaked guidance has concerning loopholes for “energy security” and may allow fossil finance to continue.

@Vanessa_Vash: At @COP26 39 institutions & countries said they would stop funding fossil fuels. One year later, only half the signatories with major finance have turned their pledges into action.” @PriceofOil is tracking them here ??https://t.co/gqQTWrR6Ob

— Oil Change International (@PriceofOil) November 16, 2022

OCI’s Laurie van der Burg detailed where countries are at. There is some good news – over the last three years, on average, there has been a 35% decrease in public finance for fossil fuels. About a quarter of this can be explained by policies that restrict fossil fuels. But for this decrease to be sustained, countries must deliver on their Glasgow pledge. G20 nations and multilateral development banks are still backing at least USD $55 billion per year in oil, gas, and coal projects, almost twice the support provided for clean energy, which averaged only $29 billion per year.

On the country level, good policies have been published by the UK, Denmark, France, Sweden, Finland, and the European Investment Bank. Belgium and the Netherlands have published policies with significant loopholes. A handful of major financier countries like Canada, Germany, Italy, the United States, Switzerland,and Spain have not yet published their policies.

There is much more to be done before countries can achieve the potential behind the statement, shifting USD $28 billion a year from fossil fuels to clean energy.

Now it is @PriceofOil‘s @LaurievdBurg: “The 40 Glasgow Statement signatories can shift $28 billion/year out of fossil fuels and into clean energy – enough to close the energy access gap. But ONLY if signatories make good on their promises.” Details here: https://t.co/wWamQ7RqNi pic.twitter.com/CyVpvgH3Yg

— Oil Change International (@PriceofOil) November 16, 2022

Optimism was to be found from the UK Government’s Louise Burrows, who talked about the UK’s journey from heavy financier of overseas fossil fuels to Glasgow Statement pioneers. The day before, in a development that would have seemed impossible a few years ago, a representative from UK Export Finance – formerly one of the worst export credit agencies in the world for funding fossil fuels – celebrated the agency’s transition into a green financier. In the last financial year, it didn’t spend a penny on fossil fuels.

Edward Okot Omoya from the East African Development Bank, a Glasgow Statement signatory developing a fossil-free policy, spoke of the need for the bank’s desire to support adaptation and clean energy in Africa, and called for other multilateral development banks to join the initiative.

The need for this shift couldn’t be more clear, as attendees heard about devastation in the Philippines. By 2030, 74 million Filipinos will be affected by sea level rise, despite the country contributing only 0.4% to global emissions. Promise Salawu from Tearfund Nigeria emphasized that clean energy could be a huge opportunity for green jobs in Africa, that this can be made possible with public finance for renewables, not fossil fuels. Diana Cárdenas from GFLAC reminded everyone that given what we know about the science, no public finance should be flowing to fossil fuels.

.@diana_cm86 of @GrupoGFLAC: "Latin America is suffering from floods ?, extreme weather events ?? and drought ??. And yet we see fossil fuels being continued to be funded by key players in the financial system." #StopFundingFossils #COP27 pic.twitter.com/Psjg0oNSkn

— Oil Change International (@PriceofOil) November 16, 2022

The final word went to Paris Agreement key negotiator Laurence Tubiana, who praised signatories who had delivered on their promises and issued a warning to those who have not, like Germany. She said, “If EU countries sign new agreements for new gas infrastructure, we will no longer lead by example.” These were important words for laggards like Germany to hear.

Tubiana ended the event with the words, “bon courage,” encouraging campaigners all over the world to keep fighting.

We are suffering from a systemic addiction to fossil fuels, which we have to cure. The IPCC, IEA +others are categorical – NOW is the time.

Closing remarks on The Glasgow Pledge to End Public Finance for Fossil Fuels #COP27 pic.twitter.com/9AgcjKrlrJ

— Laurence Tubiana (@LaurenceTubiana) November 16, 2022

As we approach the Glasgow Statement’s end-of-2022 deadline, a lot of progress has been made but there is still much work to do. Just over a year ago, it was hard to imagine an end to public finance for fossil fuels. Although that end is still ahead of us, with campaigners fighting hard all over the world to make it happen, it’s starting to seem inevitable.

The UK Government may be preening itself on ending fossil fuel investment abroad, but that still leaves the much larger investments at home (which includes UK oil- and gas-fields offshore). Large-scale exploration and production licences have been granted by the Government in the last few months. Not to mention huge fossil fuel investments by UK banks abroad – when, if at all, will COPs address this issue?