By Nina Pusic

Often hidden from public view, export credit agencies (ECAs) hold a make-or-break role when it comes to achieving the 1.5°C warming goals of the Paris Agreement and averting climate catastrophe. Their export support, in the form of loans, loan guarantees and insurance, helps domestic companies limit the risk of selling goods and services in overseas markets. ECA finance is government-backed, and often concessional, helping prop up fossil fuel projects and infrastructure which would otherwise be difficult to build. OCI data shows that if ECAs do not dramatically change course, they will push the world far beyond 1.5°C.

G20 ECAs provided 11 times as much support to fossil fuels (USD 40.1 billion a year) as for clean energy (USD 3.5 billion) between 2018 and 2020, and lag behind other public finance institutions governed by the G20 such as the multilateral development banks and development finance institutions in excluding fossil fuels from their financing. This ECA fossil financing includes projects ranging from US LNG export terminals on the Gulf Coast to Rovuma LNG production in Mozambique, each jeopardizing the environmental health of frontline communities. Now there is an important opportunity for change.

At the global climate conference in Glasgow last year many of the governments operating the world’s largest ECAs signed onto a commitment to end public finance for fossil fuels by the end of this year, but recent analysis shows that they need to seriously step up their efforts and stop dragging their feet to get on track and meet their promise within the next five months.

Aligning ECA finance with Paris: The Role of the OECD Arrangement

Over recent years momentum has been building to make this much-needed policy transition for ECAs. The foundations of this transition sprouted in 2015, when the OECD, which is the primary governing body for ECAs in the OECD countries, adopted the Coal Fired-Power Sector Understanding (CFSU). The CFSU prevented OECD-member export credit agencies (ECAs) from supporting coal-fired power plants that were less efficient unless they were in developing countries. Although far from Paris-aligned, the CFSU highlighted the potential of the OECD to respond to the growing threat of climate catastrophe. Six years later, in January 2022, the CFSU was replaced with a new prohibitive clause on export credits for new coal-fired electricity generation plants. While the prohibition clause still leaves loopholes for the financing of associated coal infrastructure, it highlights the fact that the OECD Arrangement has the power to enact policies that further align ECAs with financing a liveable and more equitable future.

The data shows that it is critical that OECD restrictions move beyond coal to also address export finance for oil and gas. Out of the $40.1 billion annually spent on ECA fossil fuel finance between 2018-2020, $36.3 billion was for oil and gas. Meanwhile, the science is crystal clear that to meet a 1.5°C warming limit by the end of the century, no new oil and gas fields can be exploited. Recent studies illustrate that 40% of already developed fields need to be shut down early, considering that committed emissions from existing energy infrastructure already jeopardize a 1.5?°C climate target. This leaves absolutely no room for export credit financing for new oil and gas fields. For OECD Members to meet their obligations under the Paris Agreement, they must also end public finance for oil and gas.

The awareness of this urgent transition of public finance actors, and especially ECAs, towards clean energy and away from dirty fossil fuels is growing. Last year at COP26, 39 countries and institutions signed a joint commitment on “International Public Support for the Clean Energy Transition” (the Glasgow Statement) to end any support for fossil fuels flowing abroad by the end of 2022, and in its place prioritize finance for clean energy. Commitment three of the Glasgow Statement explicitly references the OECD Arrangement, where signatories commit to encourage other governments and their official ECAs to end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel energy sector, which includes “driving multilateral negotiations in international bodies, in particular the OECD, to review, update and strengthen their governance frameworks to align with the Paris Agreement goals”. With over 52% of OECD member countries having committed and signed the Glasgow statement, it is prime time for action at the OECD Arrangement to raise ambition beyond ending support for unabated coal-fired power, but to also restrict and prohibit public financing of coal mining and oil and gas projects and associated fossil fuel infrastructure.

Looming threats and backsliding

Yet, several emerging threats to the successful implementation of the Glasgow Statement and robust fossil fuel restrictions under the OECD Arrangement have sprung their ugly heads as a result of the ongoing energy crisis, and Russia’s horrific War in Ukraine. In late June 2022, the G7 leaders’ statement added new loopholes to the commitment to support investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG) as “appropriate as a temporary response”. This completely disregards what the best available science tells us is necessary to mitigate climate disaster and ignores the evidence that investments in new fossil fuel developments and LNG infrastructure is not needed and no effective means to ensure reliable and affordable energy supply. Additionally, the European Union Parliament voted to include fossil gas as “green” earlier this summer under its new Taxonomy for sustainable activities, blatantly disregarding climate science and flaunting an enormous win for the fossil gas industry at the expense of a burning planet and energy affordability.

With these recent developments, ambitious climate action under OECD Arrangement faces some serious risks. For signatories of the Glasgow Statement to successfully uphold their commitments, it is essential that they work together to table robust oil and gas restrictions under the OECD Arrangement.

Glasgow Signatories: ECA Leaders and Laggards

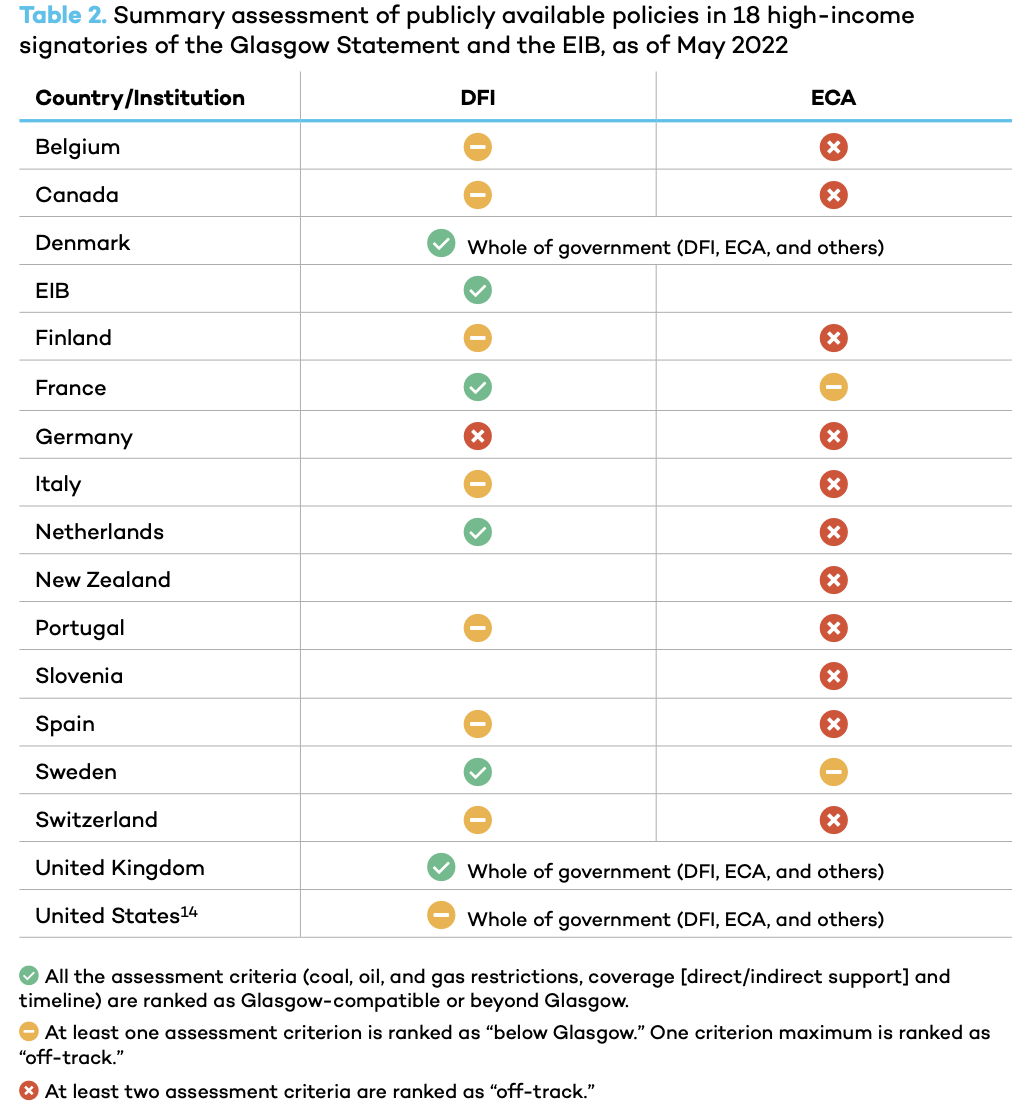

Despite the risk of backsliding, there are examples of how governments can take ambitious steps to align their ECAs with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Turning Pledges into Action, a recent report OCI wrote with the International Institute for Sustainable Development and Tearfund, evaluated where many of the Glasgow Statement signatories are at in terms of reaching their commitments. While most signatories are far behind where they need to be by the end of 2022, the United Kingdom and Denmark have both adopted policies to end fossil fuel finance of export credits within their ECAs. Now is the time for other signatories to step up their efforts, implement ambitious fossil fuel exclusion policies, and bring this political will to the OECD Arrangement.

Turning Pledges into Action, 2022 (IISD)

With less than 5 months left to implement the Glasgow Statement’s commitment to end public finance for fossil fuels, signatories cannot allow the ongoing energy crisis to stall these efforts. Even coalitions specifically designed to raise ambition on climate action, such as the Export Finance for Future (E3F) initiative, whose members have all signed the Glasgow Statement, are not demonstrating the leadership that is so desperately needed. The coalition is currently chaired by Germany, which was largely responsible for lowering the ambition of the G7 commitment to shift public finance in June.

E3F’s recent Transparency Reporting publication from May 2022 highlights that E3F members are far from reaching the ambitious targets needed by such a coalition. The transparency report outlines that despite the goal of the initiative to “align export finance with climate objectives”, E3F member countries still financed significantly more transactions in fossil fuels than in renewable energy and electric infrastructure from 2015-2020. Out of E3F’s ten members, only two, the UK and Denmark, have published policies aligned with the commitment of the Glasgow Statement. For E3F to step up to its objectives, the coalition should guarantee that each member urgently enacts robust ECA fossil fuels exclusion policies, while working as a coalition to build political will multilaterally towards tabling a proposal for oil and gas export credit restrictions under the OECD Arrangement. Our eyes will be on the Germany-chaired E3F conference that will take place on 3 November. We need to see the E3F coalition use this moment to set examples for strong implementation of the Glasgow commitment that can be followed by other ECAs, including at the OECD.

Towards a fossil-free future: ECAs as a key piece of the puzzle

For Glasgow Statement signatories to meet their commitments, and for the global community to reach the 1.5°C warming goal of the Paris Agreement and avert catastrophic climate impacts, a rapid shift in how ECAs operate is essential. Instead of proliferating the oil and gas industry, adding fuel to the fire of the climate crisis, governments must ensure their ECAs prohibit fossil fuel financing and any shift towards 100% clean, renewable energy needs to respond to the needs of local communities and protect human rights. First mover countries such as the UK and Denmark, along with initiatives such as E3F, have an opportunity to spearhead these efforts at the OECD level and beyond. Climate leadership within the OECD Arrangement to implement all-encompassing oil and gas restrictions, and to transition this funding to renewable energy projects, is a task that can’t be postponed.

what is the content of the Glasgow Statement?