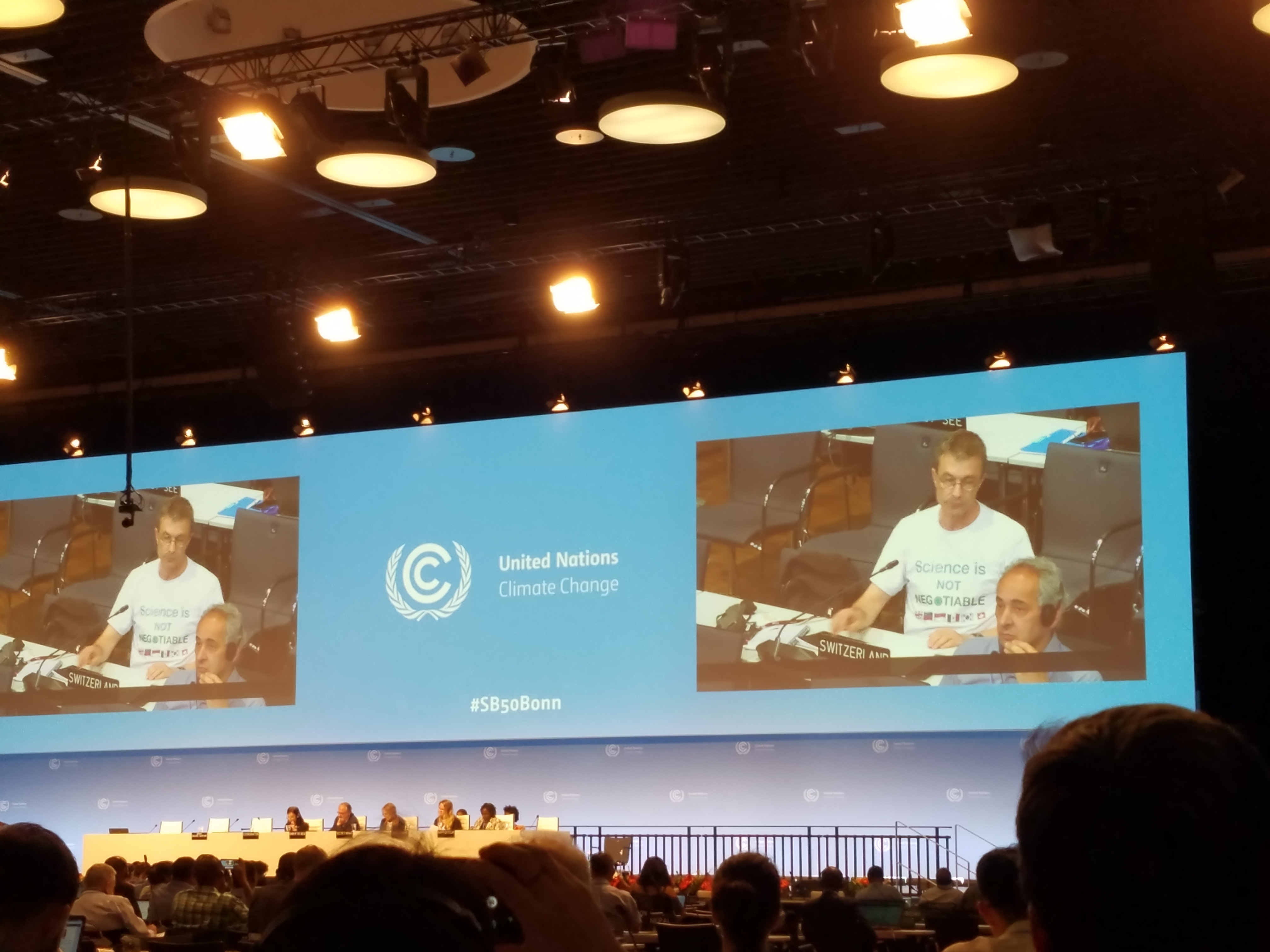

“Science is not negotiable.” Those were the words some delegates and observers wore emblazoned across their t-shirts as the latest round of UN climate talks concluded last week in Bonn, Germany.

It should be an obvious point. The unraveling of our climate systems – the heatwaves, drought, storms, fires, water shortages, and flooding devastating communities across the world – won’t slow down simply because some CEOs and politicians find the solutions, like managing a rapid phase-out of fossil fuels, to be inconvenient.

Yet, in Bonn, we saw the world’s top oil- and gas-producing countries – the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia – once again gang up to suppress discussion of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) report on 1.5 degrees Celsius (°C) of global warming in the official UN process. Despite impassioned protests from representatives of small island, Latin American, and least developed countries – delegates who said, “This is a matter of life and death” – the oil-soaked countries succeeded.

The agenda of a country like the United States in this setting is utterly transparent: serving the interests of the fossil fuel industry, at least as long as the current administration is in power. Lois Young, Belize’s UN representative, didn’t mince words in an op-ed in the Financial Times:

[T]his week, I witnessed envoys from countries with major oil, gas and coal interests — many who have shown no interest in planning for a low carbon future — saying that they reject that science. They obviously believe that with the current instability in the world no one would notice, and no one would care if they tried to exorcise the IPCC conclusions on 1.5C warming from UN climate talks and take it off the agenda.

As our recent report on U.S. oil and gas production showed, the industry is gearing up to drill and pump more oil and gas out of the United States than any other country between now and 2050. These plans would pitch a giant wrecking ball through the Paris Agreement, unleashing the carbon pollution equivalent of nearly 1,000 coal plants.

But what about other fossil-fuel producing and/or high-emitting jurisdictions that expressed support for science last week in the negotiating rooms of Bonn?

For example, in one negotiating session that I witnessed, delegates from Canada, Norway, and the European Union endorsed a proposal from the Alliance of Small Island States to hold further workshops unpacking the IPCC’s 1.5°C special report and its implications for meeting the Paris Agreement goals. Are they planning for the carbon-free future that science demands?

Unfortunately, affirming that “science is not negotiable” in the halls of a UN conference center and acting on that fact in one’s own policy decisions can be two different things.

Let’s look at some examples from Canada, Norway, and still-EU member the UK:

- Less than 24 hours after declaring a “climate emergency,” the federal government of Canada, under the leadership of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, gave its blessing to a massive new pipeline expansion to export more tar sands oil. On top of violating First Nations’ rights and risking water resources, the project could lock in an additional 130 million tonnes of carbon pollution annually.

- Norway has gained some kudos of late for divesting their sovereign wealth fund from oil and gas exploration and production companies, even as it stays invested in oil majors. At the same time, Norway continues to license new oil and gas extraction in the North Sea. Already the world’s seventh-largest exporter of carbon pollution, and one of the world’s wealthiest fossil fuel producers, Norway has no plan to phase out its oil and gas production. Yet any equitable pathway to achieving the Paris Agreement – and the IPCC report points to equity as key – would see wealthy producers like Norway moving first and fastest to wind down their extraction.

- The UK became the first national parliament to declare a “climate emergency.” Yet, this summer the UK is set to issue its 32nd licensing round for oil and gas extraction. UK subsidies and support aimed at maximising oil and gas extraction are on track to unleash more carbon pollution than the country will save from phasing out coal-fired power.

Climate science shows that there is a finite limit to the carbon that we can emit while keeping warming below 1.5°C. We are rapidly hurtling towards that limit. The IPCC Special Report indicates that staying below 1.5°C of warming will require phasing out fossil fuel pollution beginning now so that net carbon emissions zero out by 2050. Intentionally planning to wind down fossil fuel extraction and burning at the pace required to meet that target, and stay within carbon budget limits, would be the rational approach in response to that science.

In fact, studies indicate that our fossil fuel system is too big already. Analysis by Oil Change International shows that existing fossil fuel extraction projects – where the capital is sunk, necessary wells have been (or are being) drilled, and the related infrastructure built – hold enough oil, gas, and coal to take the world well above 1.5°C and exhaust a 2°C carbon budget. The upper bound of the Paris Agreement is well below 2°C. In fact, some countries will need to wind down their fossil fuel production earlier than planned to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Studies examining this issue from the other end of the supply chain – where fossil fuels are burned – come to the same conclusion: too much is already built.

Unless countries are willing to risk the survival of millions of people on unproven, potentially unviable technologies to suck carbon back out of the atmosphere, they need to stop financing and permitting fossil fuel infrastructure designed to emit more pollution and instead invest in solutions to phase it out.

Some jurisdictions and institutions are taking steps in the right direction. Costa Rica has extended its moratorium on all oil and gas licensing as part of its comprehensive plan to decarbonize by 2050. New Zealand has banned new licenses for offshore oil and gas exploration, with Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern calling it key to “ensuring there is a just transition to a clean energy future.” Sweden has already phased out fossil fuels from all of its public finance.

This is the new standard for climate leadership as we head towards the next big global climate summits, including the UN Secretary General’s meeting this September in New York and the 26th Conference of Parties this December in Chile. Defending science is not enough – what counts is acting on the science to manage a rapid and just transition off of fossil fuels.