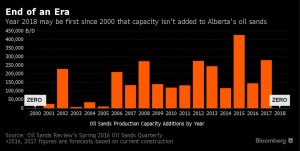

It’s a small simple chart which has a huge significance for Canada and the climate.

According to a Bloomberg analysis of recent industry data, two decades of expansion in the dirty tar sands of Alberta is set to come to an end in 2018.

They conclude “no projects currently under construction are set to be completed that year or beyond.”

Due to the collapse in the oil price, the tar sands producers are seriously struggling. There is too large a gap between the high cost of production of the tar sands and the current price of oil for many to invest over the long term.

It is worth remembering that the crisis in the tar sands comes at a time when there is growing public pressure to build a clean energy future that does not hitch Canada’s economy to the destructive boom and bust cycle of oil.

This concern can be seen in the growing opposition by front line communities across the country to new tar sands infrastructure such as pipelines, and for support for building a safer, renewable energy economy.

For the industry, these concerns would be easier to dismiss if it sat on a cushion of high oil prices.

But the cushion has burst.

Because of the oil price plunge, some half a million barrels a day of planned production capacity has been cancelled or put on hold over the last eighteen months.

Around this time last year, Oil Change International (OCI) identified some 39 tar sands projects delayed or on hold.

The pain continues. In recent days, two Calgary-based smaller tar sands producers have announced multimillion-dollar fourth-quarter losses. Sunshine Oilsands reported a $326 million net loss; whilst Connacher Oil and Gas reported a loss of $56 million.

Indeed, last month CBC reported how “increased competition, low prices and climate change policy have put the future growth of Alberta’s oilsands in doubt — and that has the federal government concerned”.

They also reported that there was concern about investment in the sector, post-2020. Quoting a report by the Federal Department of Finance, it suggested that further tar sands expansion could be “vulnerable”.

The government report outlined how “As the marginal supplier of world oil, because of its high costs and climate change footprint, Canadian oilsands would face the brunt of the post-2020 reduction in oil demand (despite the price approaching $80”.

Allan Dwyer, a finance professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary told CBC news: “The report confirmed my main concern — which is, long term, the oilsands are not viable.”

The tar sands are not viable on price, and they also fail the climate test.

As any regular reader of this blog or any reports from OCI will know that as the third largest reserves in the world, with projects that lock in a half a century of pollution once built, the dirty tar sands are incompatible with keeping global warming to internationally acceptable limits.

It is a conundrum that the Government has long failed to address: At the end of last month, for example, the Canadian Press reported how the “Federal Environment Minister won’t say if Canada can develop oilsands and meet climate targets”.

Increasingly, civil society organisations such as OCI have been calling for a “climate test” to be undertaken as a key part of meeting those targets.

As Hannah McKinnon from OCI explains: “The crux of the climate test is using our actual climate goals (limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees C) to define the types of infrastructure that are going to be economically viable, necessary, and appropriate over the coming decades in the safe climate future we are committed to.”

The bad news for the Canada is that the tar sands sector fails the test badly.