As another round of UN climate negotiations wraps up today in Bonn, expectations are taking shape for the end of the year Paris conference where countries will have yet another chance to prove they are ready to take on one of the world’s greatest challenges.

Nobody (with the possible exceptions of Canada, Australia, and Japan who have become the global climate laggards) wants another Copenhagen fiasco. And you can bet that countries will spend the coming months tripping over each other to announce new efforts to avoid arriving to Paris in December empty handed.

There is no shortage of questions to be asked with the pre-conference race to the microphone; Will it stick? Is it real? Is it greenwash? Is it new? Is it a solution? And so on. But one question that we would add to the list – in particular to the G20 countries: Why not kick the fossil fuel subsidies habit? If you don’t even go for this low hanging fruit, how can we trust you are serious about more challenging efforts?

Fossil fuel subsidies are pervasive. And the worst of the bunch are the subsidies that encourage exploration and expansion of new fossil fuels, AKA, unburnable carbon. The world already has enough oil, coal and gas at its fingertips to do serious climate damage (in fact, well over 70% of what we already have access to has to be kept in the ground) – so propping up industry efforts to find more is nothing short of crazy.

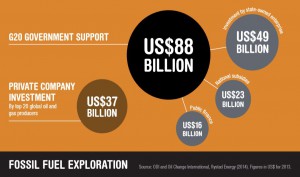

Oil Change International published a study in November with the Overseas Development Institute that found that G20 countries are spending $88 billion dollars on exploration subsidies every year. And with the shifting economics of high cost, high carbon, high risk fuels, this money is what keeps much of this hunt for unburnable carbon going. Without these outdated subsidies, these projects would be right where they should be: unprofitable. And these exploration subsidies are just a piece of a much bigger pie – our analysis shows that fossil fuel subsidies globally amount to between $775 billion and $1 trillion dollars each year.

Further to this is a new analysis we published last week with NRDC and WWF that found that public finance has played a significant role in supporting coal projects over the last 8 years. The report shows that between 2007 and 2014, more than US $73 billion – or over $9 billion a year – in public finance was approved for coal.

Not only is it hypocritical for countries standing at the mic to tell the world they are tackling climate change while they are bankrolling things like fossil fuel exploration and the dying coal sector, but it also has to make you question their credibility. G20 countries already promised to put an end to these types of ‘inefficient’ subsidies in 2009. And so far not one of them has succeeded in wiping their budget free of handouts and tax breaks to some of the richest companies in the world, whose business models depend on climate destruction.

If countries can’t even manage the obvious action of pulling the plug on public money for the hunt for more unburnable carbon – how can we take them seriously on other policy change? Perhaps it is indicative of the tight grips the fossil fuel industry has on governments, but the jig is up. Everyone from the International Energy Agency to the Economist has called for an end to these subsidies. It turns out that not only are they bad news for the climate, but they are bad economic policy too.

There is space in the climate talks to pressure countries to #StopFundingFossils. Whether it is in the long-term goal, or as part of an effort to find so-called innovative financing for climate adaptation and loss and damage, or as an option for where to find support for shifts to the decarbonized economy that is now the hot topic in the hallways of the climate conference – fossil fuel subsidies are a clear and specific target for all kinds of reasons.

As we watch countries try to prove that they will be on the right side of history when it comes to the Paris climate talks, we would find it much more convincing if they stopped pouring billions into digging themselves deeper into the hole they claim to be trying to get out of.