Last week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) took a small, crucial step towards fixing its flagship World Energy Outlook (WEO). For the first time, the IEA included a “case” (a sort of mini-scenario) that could be consistent with getting to net zero by 2050 and limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (ºC).

Last week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) took a small, crucial step towards fixing its flagship World Energy Outlook (WEO). For the first time, the IEA included a “case” (a sort of mini-scenario) that could be consistent with getting to net zero by 2050 and limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (ºC).

Securing this pivot is a critical signal that the IEA is hearing the growing calls from a broad group of stakeholders demanding a central, high ambition scenario front and centre in WEO.

Now they have to finish the job. WEO 2020 is only a small step forward when the world needs a giant leap. This new case, called Net Zero Emissions 2050 (NZE2050) stops at 2030, is relegated to the margins within the WEO, and could depend on significant levels of carbon-dioxide removal beyond 2050.

In this analysis, we summarize the background to this step forward, highlight some key points from NZE2050, explore the problems and gaps that remain in WEO 2020, and outline what the IEA needs to do in 2021 to avoid this step forward becoming a dead end.

IEA business as usual is a roadmap for climate disaster

Instead of providing a robust and credible pathway toward phasing out fossil fuels and achieving global climate goals, past IEA analysis has provided cover for fossil fuel investments that add up to climate disaster. For years, the WEO’s central Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS) has set out a pathway towards climate breakdown.

In the face of mounting pressure from governments, business leaders, energy experts, and climate scientists to fix the WEO, the IEA made minor changes (as set out in our discussion paper, Still Off Track). Last year’s WEO changed scenario names and tinkered at the margins without delivering real reform. The IEA itself stated in WEO 2019 that STEPS would lead to a catastrophic 2.7ºC to 3.2ºC of global warming. For the first time, mainstream media seriously challenged the IEA on climate – as did an ever growing group of experts, academics, investors, influencers and even diplomats.

Then, in January 2020, the IEA called for a “grand coalition” with Big Oil and Gas. Instead of fixing the problems with its own analysis, the IEA launched a public relations effort that closely aligned with the oil and gas industry’s spin. (It can often be hard to tell IEA boss Dr. Fatih Birol apart from a Big Oil and Gas CEO.)

As the tragic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic began to unfold, with people worldwide facing extreme health, social and economic impacts, the oil and gas industry (already showing signs of financial decline) entered a chaotic, unmanaged decline, laying off workers, cancelling projects, and abandoning polluting infrastructure entirely.

Dr. Birol responded by urging governments worldwide to place clean energy at the heart of their stimulus packages. The IEA sought to position itself as a key resource to help governments to shape effective, climate-friendly responses to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis.

Then, in May 2020, over 60 global climate leaders wrote to Dr. Birol, urging him to ensure that the IEA lived up to this clean energy recovery rhetoric by placing a 1.5ºC scenario at the centre of this year’s WEO. They argued:

Effective stimulus measures will ensure that new clean energy replaces fossil fuels, rather than adding to them. They will map out a pathway for a just transition to a net-zero emissions economy, with tremendous potential for job creation at scale. Bold, not incremental, action is required to transform energy systems at the scale and pace required.

However, the IEA’s June 2020 Special Report on Sustainable Recovery again fell short on climate ambition. While the report ultimately included some positive conclusions – namely, that energy efficiency and renewable energy investments are the best recovery tools – it lacked a cohesive climate lens, slipping back into the IEA’s destructive business as usual.

NZE2050: A crucial step forward

In this context, NZE2050 is a crucial step forward. Finally, the IEA has responded to growing calls from people, investors, civil society organizations, and global climate leaders. For the first time, this year’s WEO includes the beginnings of what could become a 1.5ºC-aligned scenario.

In the IEA’s words, NZE2050 is “the first detailed IEA modelling of what would be needed in the next ten years to put global CO2 emissions on track for net zero by 2050.”

However, this case is not a full scenario. Whereas the other IEA scenarios run to 2050, NZE2050’s modeling only extends to 2030. This is what makes it a case or mini-scenario, not a full scenario.

In the NZE2050 case, global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from energy and industrial processes fall to 20.1 gigatonnes (Gt) in 2030. This level is 6.6 Gt lower in 2030 compared to the IEA’s most ambitious full scenario, the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS) – that is, almost 25% lower. As with the SDS, it “simultaneously delivers universal access to energy by 2030 and a major reduction in air pollutant emissions”.

IEA: Energy and industrial process CO2 emissions and reduction levers in WEO 2020 scenarios, 2015-2030

Source: IEA WEO 2020

This 2030 estimate of CO2 from energy and industrial processes sits between the illustrative P2 and P3 scenarios in the IPCC’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC (SR1.5). However, NZE2050 assumes a higher level of population and economic growth than in most of the scenarios assessed by the IPCC in SR1.5.

But the WEO still needs fixing

The inclusion of NZE2050 is an important start – but in its current form, it is not enough to fix the problems. We have identified six major problems that need to be fixed:

- The WEO still centers climate failure;

- The IEA misdirects investment into fossil fuels;

- NZE2050 only includes modeling to 2030;

- NZE2050 goes easy on fossil gas and coal;

- The IEA over-relies on negative emissions beyond 2050; and

- Ultimately, NZE2050 lacks transparency.

In this section, we analyse each of these problems in turn.

The WEO still centers climate failure

The IEA still focuses its attention primarily on the catastrophic STEPS scenario – a pathway towards 3°C of warming. Though the SDS receives more attention than in previous WEOs, and mentions of “net zero” and “1.5C” have increased significantly, NZE2050 receives far less attention than SDS, which in turn receives less than STEPS.

In particular, WEO 2020’s Executive Summary still places the emphasis on pathways that would entail unacceptable levels of climate destruction and human loss: it references NZE2050 only four times and refers to STEPS 20 times.

Significantly, even the limited NZE2050 data is omitted from the data projection tables in WEO 2020. These tables are influential, because governments and investors use them to interpret, extrapolate, and apply the IEA’s analysis.

This focus towards failure is reflected in much of the IEA’s framing. The IEA continues to count the costs of climate action, repeatedly highlighting the difficulty of cutting carbon pollution in line with NZE2050, without any acknowledgement of the catastrophic, immeasurable human, ecological and economic costs of failing to achieve that 1.5ºC goal.

The IEA misdirects investment into fossil fuels

The consequence of the IEA marginalizing 1.5°C in WEO 2020 is that the IEA misdirects investment. The figure below is from the WEO 2020 chapter on fuel supply, and shows projected oil demand under SDS and STEPS compared to projected supply from existing versus new fields.

The IEA did not include NZE2050 in this graph – despite having the relevant data in NZE2050. Consequently, we have superimposed the IEA’s projection of oil demand in 2030 under NZE2050 (65 mb/d) onto the figure. This shows that virtually all new field investment under the SDS and STEPS would be incompatible with 1.5°C, assuming some continuing investment in existing fields.

As a result, the IEA could potentially misdirect trillions of dollars into new fossil fuel investment by sidelining its new NZE2050 case.

NZE2050 only includes modeling to 2030

The new case is not a full scenario. Whereas STEPS and SDS run through to 2050, NZE2050 ends in 2030.

A mini-scenario that ends in 2030 does not provide the information that governments and investors need. Energy infrastructure being built now will have a lifespan that extends beyond 2030, so governments and investors seeking to align capital expenditure decisions with 1.5ºC need information that goes beyond 2030. What’s more, several governments are making energy and climate policy decisions now that go beyond 2030. For example, the UK Climate Change Committee is due to publish advice on setting the country’s 2033-2037 carbon budget in December 2020. This will be the first UK climate budget set towards the country’s net zero 2050 goal, so could be expected to parallel NZE2050 – except NZE2050 provides no information about the budget period. Several other countries have similar laws and processes in place.

WEO 2020 does not provide a clear rationale for why NZE2050 is not a full scenario. The IEA argues that NZE2050 ends in 2030 because:

Decisions over the next decade will play a critical role in determining the energy and emissions pathway to 2050.

This is true – but these decisions will need to consider the energy and emissions pathways to 2050. The IPCC SR15 makes it inarguable that the decisions made this decade will determine our success or failure in limiting warming to 1.5ºC. That is precisely why it is so important that NZE2050 is built out into a full scenario.

It could be argued that the IEA simply did not have time or capacity to complete a full, new scenario this year, in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Dr. Birol says in WEO 2020’s foreword that the decision to include NZE2050 was made in early 2020. If so, there can be no excuse not to build it into a full, central scenario for WEO 2021.

This is especially because the Paris Agreement was five years ago. If this was WEO 2016, it would be reasonable to say that there wasn’t time to build a 1.5ºC scenario. The IPCC SR1.5 is two years old. The IEA has had years to grapple with the urgency and importance of limiting warming to 1.5ºC.

NZE2050 goes easy on fossil fuels

Comparing NZE2050 to pathways assessed by the IPCC that prioritize early action, equity, and relative precaution on carbon-dioxide removal shows that even in this new case, the IEA is still going relatively easy on fossil gas and coal. Despite acknowledging that existing fossil fuel infrastructure alone “would ‘lock in’ emissions for decades to come” and blow through the 1.5ºC climate goal, the IEA still manages to avoid engaging with the need to cut oil, gas, and coal production.

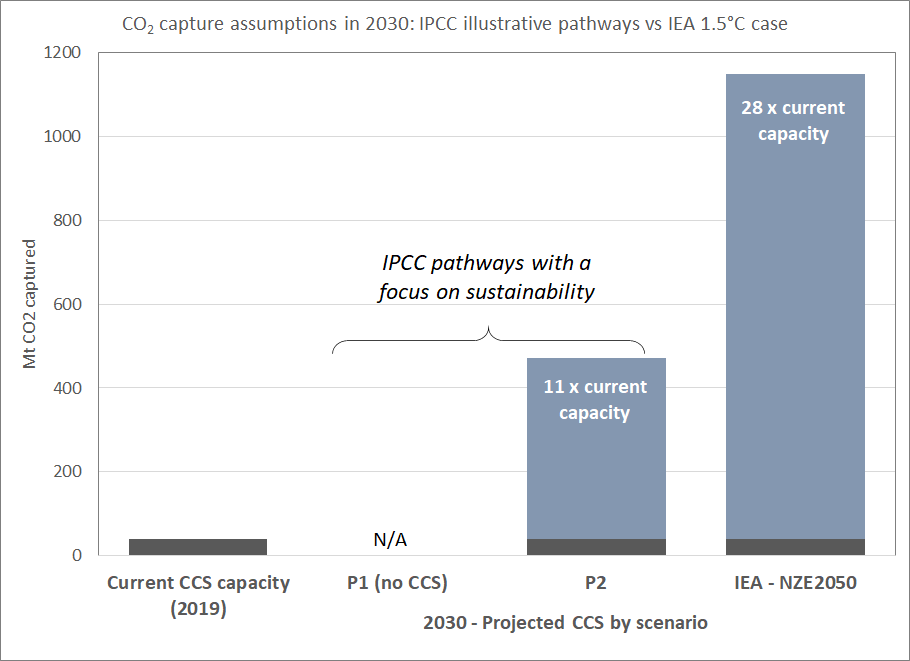

When it comes to fossil gas and coal, NZE2050 has significant misalignment from the P2 illustrative pathway from IPCC SR1.5, despite the IEA claiming that the two are “similar”. NZE2050 has a significantly slower decline in fossil gas and significantly higher reliance on carbon capture and storage (CCS) in 2030, compared to both the IPCC P1 and P2 pathways.

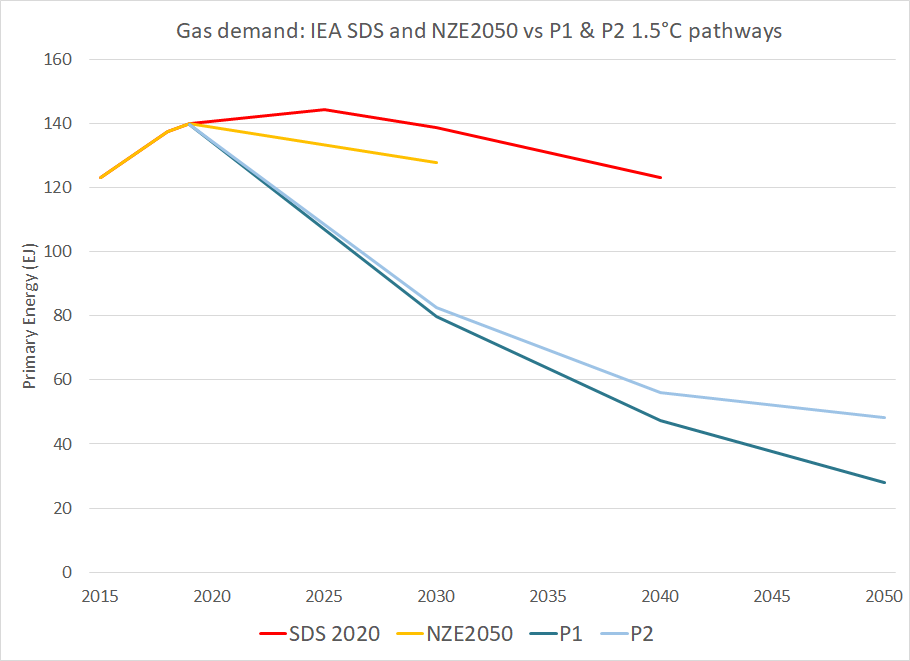

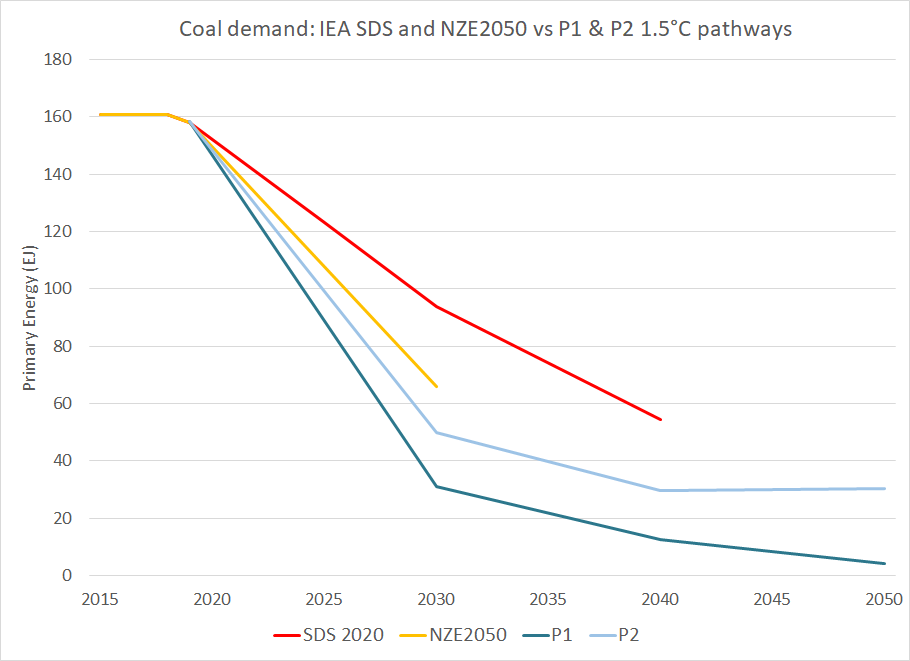

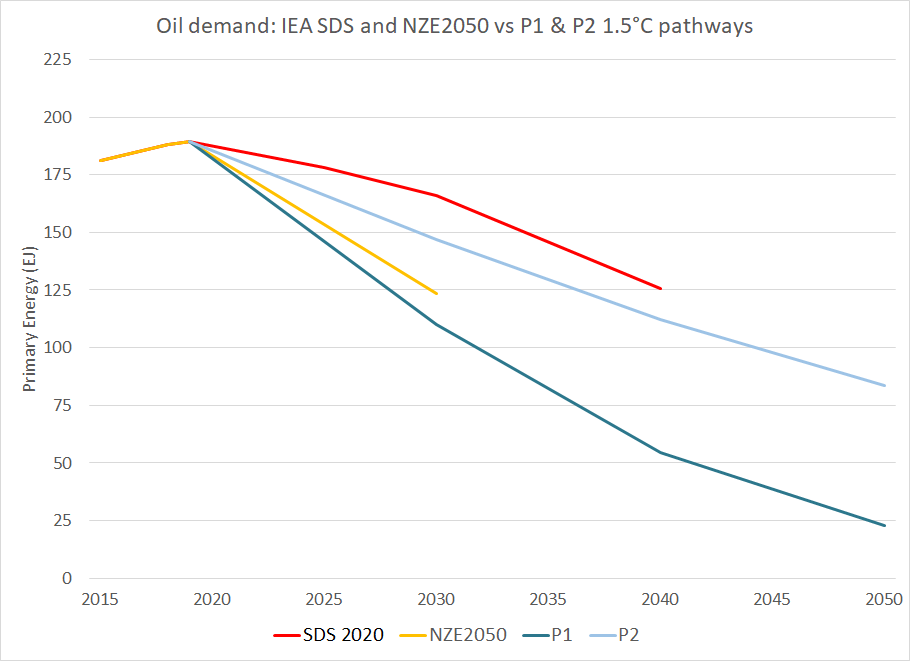

The three figures below compare the 2030 trajectory for oil, gas, and coal demand in the NZE2050 to that of the SDS and to the P1 and P2 pathways featured in the IPCC SR1.5. We choose P1 and P2 for comparison because they respectively rely on zero and relatively limited amounts of bioenergy with CCS, a largely unproven negative emissions technology, to compensate for excess fossil fuel use.

Sources: WEO 2020 Table A.3: Energy demand (SDS) and Figure 4.5 (NZE2050); IPCC SR1.5 IAMC Scenario Explorer (P1 and P2)

These are major differences. As shown in these figures, in the P1 and P2 pathways featured in the IPCC 1.5°C Special Report fossil gas demand is more than 40% lower than 2019 levels by 2030. In the IEA’s NZE2050 case, gas demand decreases by only 9% by 2030.

These differences are reflected by very large misalignment between the IEA and the same illustrative IPCC pathways on the levels of CCS reliance in 2030, as shown in the below figure.

Sources: WEO 2020, Ch. 4; IPCC SR1.5 IAMC Scenario Explorer (P1 and P2)

NZE2050 assumes that CCS will draw down 1,150 Mt of CO2 emissions in 2030. This is in part made necessary by the IEA’s excess reliance on fossil gas. That level of CCS would represent a 28-fold increase over current global CCS capacity, and is 2.5 times greater than the amount of CCS assumed in the P2 pathway in 2030.

The reality is that we need a managed decline in fossil fuel production. By avoiding this reality, the IEA is still providing cover for oil, gas, and coal expansion and investment.

The IEA over-relies on negative emissions beyond 2050

What’s more, the IEA is still playing fast and loose with IPCC science and claims around negative emissions reliance in the WEO.

In WEO 2020, the IEA repeats its previous assertion that the SDS “limits the temperature rise to 1.5°C in 2100 on the assumption that negative emissions technologies are deployed in the second half of the century.” It makes similar claims in its WEO 2020 FAQ. This ignores the temperature overshoot and sustainability risks emphasized by the IPCC.

In response to the same claims in WEO 2019, IPCC SR1.5 Lead Author Dr. Joeri Rogelj stated:

The amount of CO2 removal needed after 2070 to meet 1.5°C would go well beyond the sustainable limits that the IPCC has identified.

In addition, the IEA claims that the new NZE2050 case would not rely on “a large level of net negative emissions globally,” but does not provide the data to back up that claim. It is unclear how NZE2050 would align with 1.5°C in the long run without significant reliance on carbon-dioxide removal. While NZE2050 does not rely on significant levels of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) up to 2030, the IEA does not disclose its assumptions about carbon-dioxide removal post-2030.

The IEA pinned the 2030 CO2 emissions of NZE2050 to the median outcome of 53 1.5ºC pathways assessed by the IPCC. While on the surface this sounds reasonable, Joeri Rogelj notes that interpreting the IPCC’s ensemble of scenarios as a statistical sample like this is methodologically unfit and contrary to good practice guidelines. Among those 53 pathways, the range of cumulative CO2 removal via BECCS from 2016 to 2100 spans 0 Gt to more than >1,000 Gt. Many rely on levels of carbon dioxide removal that go beyond feasibility and sustainability limits cited by the IPCC. If the IEA had set out to minimize reliance on risky, unproven technologies, it would have chosen specific pathways that actually do that as a model for its own.

The illustrative P1 pathway in the IPCC SR1.5 report, which does not rely on BECCS, is at 16.5 Gt CO2 in 2030. That is 3.6 Gt lower than the IEA’s new scenario.

Ultimately, NZE2050 lacks transparency

One difficulty in analysing or using NZE2050 is that much of the underlying data is not available.

All the data that sits behind NZE2050 should be made available with the same detail as the other WEO scenarios, STEPS and SDS.

Without this data, the basis for many of the IEA’s assumptions and conclusions is not clear.

How the IEA can #FixTheWEO in 2021

These problems are easily fixable. By including NZE2020 in WEO 2020, the IEA went part way, but this must be a starting point not a final outcome. In WEO2021, the world needs the IEA to finish the job, and build out the NZE2050 case into a full, central scenario.

Countries and companies that want to align their energy policies and investments with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5ºC ambition need energy scenarios and advice compatible with 1.5ºC. These key WEO users need pathways that allow them to plan for success, not further entrench fossil fuels.

To provide the advice that governments and investors need to make decisions that align with 1.5ºC and achieve the ambition of the Paris Agreement, the IEA must take the opportunity in WEO2021 to:

- make NZE2050 the central scenario in WEO 2021, instead of making climate failure the default option;

- build NZE2050 out into a fully fledged scenario that aligns with a precautionary pathway for staying within 1.5ºC out to 2050, counting the costs of inaction as well as the costs of action; and

- make its underlying data transparent and accessible to investors, governments, and other people and organizations who use WEO.

These are far from impossible asks. They are logical next steps with real support from governments, civil society, and investors – and they are necessary to enable the IEA to play a part in unlocking a clean energy recovery that meets our global climate goals, and protects people, especially in the world’s most vulnerable and structurally oppressed communities.

What’s more, by taking these steps, the IEA will force itself to get real about how fast we need to phase out oil and gas.

If the IEA doesn’t want its new NZE2050 case to become just a dead end, it needs to finish what it has started and fix the WEO in 2021.