Speaking truth to power has always been difficult. Holding the powerful to account is even harder. And seeking justice through the courts is a road not for the faint-hearted. For days can become weeks. Weeks can become months. Months can become years. And years can become decades. Before long a quarter of a century can pass. And still justice remains a distant elusive dream.

It is now twenty-five years since the killing of the Nigerian writer, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and eight other Ogoni, who were murdered for their campaign against the oil giant Shell, whose rampant double standards and pollution had caused the Ogoni community to mobilise in the early nineties.

Since then, many people have tried to hold Shell to account for its complicity in murder and its rampant pollution. Just three months ago, I wrote that “It is appalling that no one in those intervening years has been found guilty of the extra-judicial murder of Saro-Wiwa and the others.”

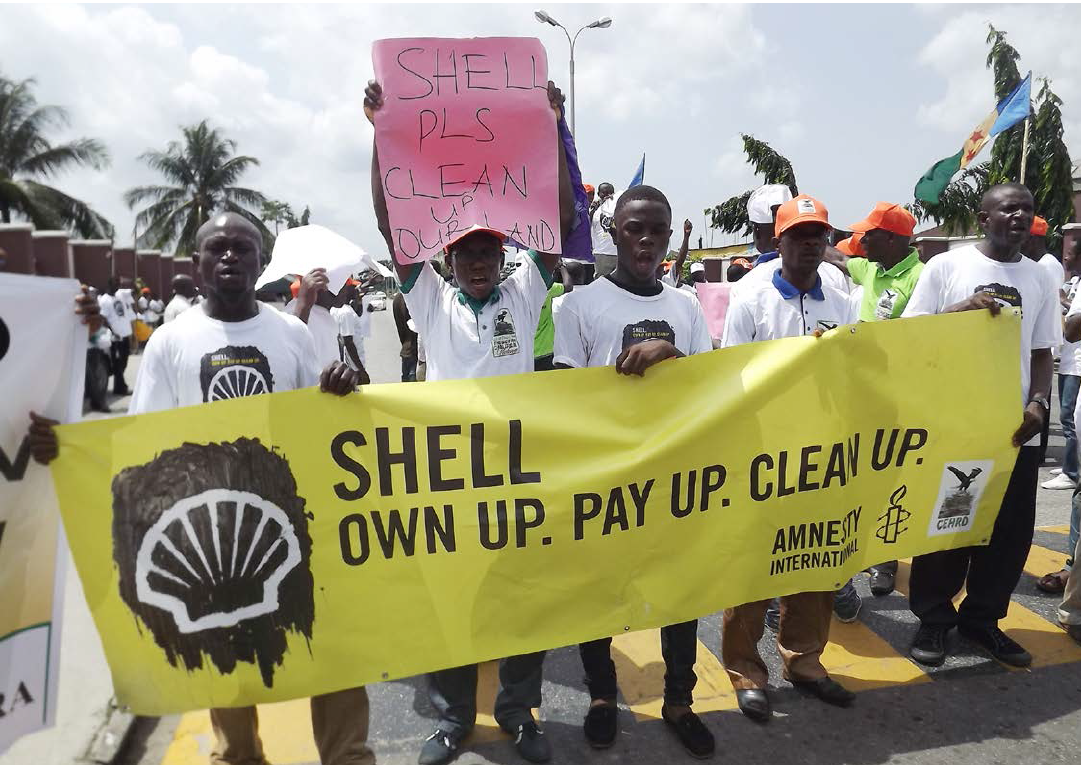

It is equally appalling that Shell has not tried to bring closure to the issue by admitting guilt, paying compensation and adequately and promptly cleaning up its toxic mess and legacy in the Niger Delta, and in particular in Ogoni.

But hopefully justice is coming. And 2020 is the year that the chickens finally come home to roost for Shell. It can evade justice no more. It has run out of places to hide.

Saro-Wiwa wrote in his closing testimony at the trial of the Ogoni 9 that: “I and my colleagues are not the only ones on trial. Shell is here on trial and it is as well that it is represented by counsel said to be holding a watching brief. The Company has, indeed, ducked this particular trial, but its day will surely come … The crime of the Company’s dirty wars against the Ogoni people will also be punished.”

Shell’s day is coming.

In 2002, the widow of one of the others, Esther Kiobel sued Shell in the USA, where she had been granted asylum. Over ten years later, the US Supreme Court ruled that it did not have jurisdiction over the case, meaning US courts never got to examine the facts of the case, either.

Three years ago, Esther Kiobel filed a new civil case against Shell in The Netherlands, supported by Amnesty International. The case was brought along with other widows: Victoria Bera, Blessing Eawo and Charity Levula. They demanded compensation and an apology from Shell.

Last year, the District Court of The Hague heard from witnesses, including those who testified that they had been bribed by Shell to testify against Saro-Wiwa and the others. As Mark Dummett from Amnesty, who was in court that day, tweeted at the time:

(for further background on the trial of the Ogoni 9, see the work of Michael Birnbaum QC. An English lawyer, he observed part of the trial. https://t.co/BVrGDAkgjA)

— Mark Dummett (@MarkDummett) October 8, 2019

The court is expected to rule this year, probably in March. If, and it remains, a big if, Shell was found guilty before the 25th Anniversary on the 10th November this year, it would be a stratospherically symbolic moment for all those who have fought for justice for those long years, not least Esther and the other Ogoni 9 widows.

But the Kiobel case is not the only legal action Shell faces this year.

In a report published today, Amnesty, who more than any organisation in recent years had stood steadfast in their dedication to hold Shell to account, outline four other areas where the oil giant could be in trouble: As the report outlines:

- In May 2020, a final hearing is also expected in the first cases brought against Shell in a European court over its environmental record in Nigeria. In 2008, four Nigerian farmers and Friends of the Earth Netherlands filed three separate claims in the Netherlands against Shell over damage caused by oil spills. It is worth remembering that these cases marked the first time that a Dutch multinational had been sued in a Dutch court over the operations of its overseas subsidiaries;

- In June 2020, the UK’s Supreme Court will hear an appeal brought by two communities, Ogale and Bille, in another pollution-related case. The court will decide whether it can proceed on the critical issue of whether the Shell parent company is liable for the actions of its subsidiary in Nigeria. Shell claims that the parent company is not responsible for the actions of its subsidiary even though it owns 100 percent of the shares and receives all the profits that it makes. The company has tried to make the same argument for decades, to try and distance itself from its subsidiary;

- In 2008 there were two massive oil spills in a creek close to the Bodo community. Shell settled with the community in 2014 but has yet to clean up Bodo’s contaminated waterways. If the pollution is not cleared by mid-2020, the case will be referred back to the UK High Court;

- Meanwhile Prosecutors in Italy are bringing a criminal case over the alleged involvement of Shell, and the Italian oil multinational Eni, in a 1.3 billion US dollar bribery scheme connected to the transfer of a Nigerian oil licence. The case is also being investigated by law enforcement agencies in the UK, the Netherlands and Nigeria. If found guilty, some former members of Shell staff face jail and the company faces financial penalties.

As it has done and will always do, Shell denies the claims.

The legal ramifications of any of these cases will be felt far and wide too, if the plaintiffs are successful. No longer could the powerful be complicit in murder or pollution or bribery with impunity.

As Amnesty notes in its report: “These cases are not only important for the individuals and communities involved. They could set important precedents on the responsibility of companies for their overseas operations, which would open the way for further litigation not only against Shell but other multinational corporations as well.”

Shell could have admitted guilt decades ago. But it did not. It chose to hide. It chose to bury the truth. It chose to cause more pain to those who want the suffering to end.

Even if Esther Kiobel and the other widows are successful this year, justice will come too late for Ken Saro-Wiwa’s son, Ken Wiwa, who has now tragically passed away too. Five years ago, Ken Junior, as he was known, wrote in the Guardian:

“Sometimes it seems as if 10 November 1995 was another era. In some ways it was, and in others it feels like it was just yesterday. Between the disabling nature of his death and the enabling tests of time, one thought still sustains me: it is the old idea that the arc of the moral universe may be long, but it still bends towards justice.”

Justice must come. Shell must pay. Shell can run from the crimes of its past no more.