Argentina is on the brink of an oil and gas production explosion, with its top shale plays forecasted to vastly increase oil and gas production in the country through mid-century. Up first and largest is Vaca Muerta – literally translated from Spanish as ‘Dead Cow’ – a massive fracking play in northern Patagonia that covers an area inside Argentina the size of Belgium.

The annual summit for the Group of 20 countries,[1] which will be held in Buenos Aires at the end of November next year, seems set to serve as a boost for this development. Already in preliminary discussions, fossil gas is a key point being taken up by governments as they look towards the summit. A side event highlighting the Role of Natural Gas is planned ahead of the second Energy Transitions Working Group (ETWG) meeting and the G20 Energy Ministerial on June 15 – a key moment for energy issues on the road to the summit.

While all G20 governments – with the notable exception of the United States – claim to uphold the Paris Agreement commitments on climate change, G20 energy statements have consistently voiced support for the development of natural gas. This is a contradiction, as meeting the Paris goals of holding global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius means that no new fossil fuel extraction or transportation infrastructure should be built.

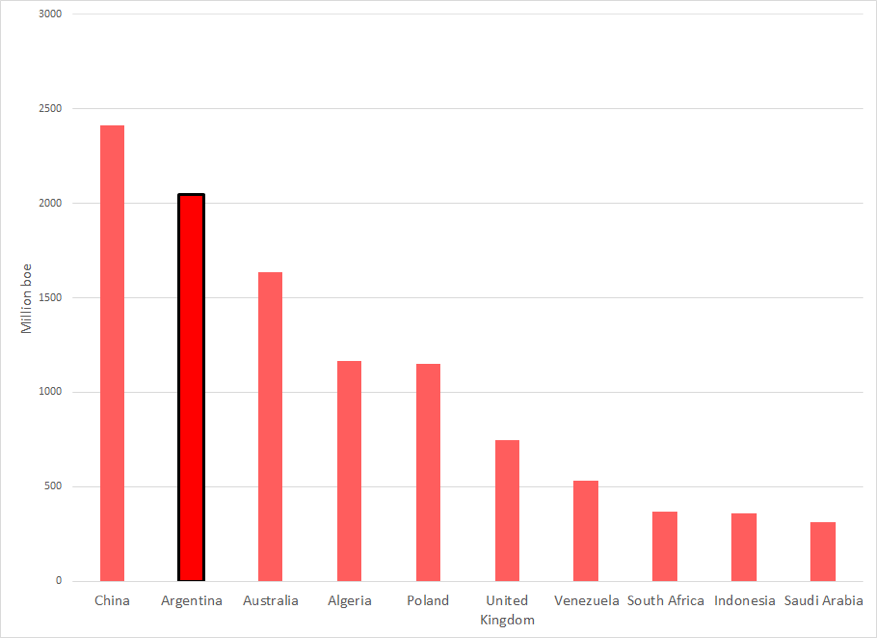

According to Rystad Energy estimates, over the next 20 years, Argentina could be second-biggest producer of oil and gas from shale plays outside of North America (see Figure 1). This production would be driven by development of Vaca Muerta. Vaca Muerta could be a proving ground for the expansion of significant new fracking development in South America, opening a whole new carbon frontier.

Figure 1: Top Countries (outside of North America) by Potential Oil and Gas Production from Shale Plays Over the Next 20 Years (2018-2037)

Source: Rystad Energy UCube, December 2017

Production out of Vaca Muerta has already started, with companies such as Chevron, ExxonMobil, Total, BP, CNOOC, and others already working to secure access to oil and gas resources. Less than 5% of the formation has already been developed, but if oil companies are allowed to continue, Vaca Muerta will become a major center of fracking with significant environmental impacts. Development of the project will require vast amounts of direct inputs like water and sand, and it will also trigger the construction of dozens of infrastructure projects – aqueducts, trains, roads – to make the project functional and carry the resulting resource to its final destination.

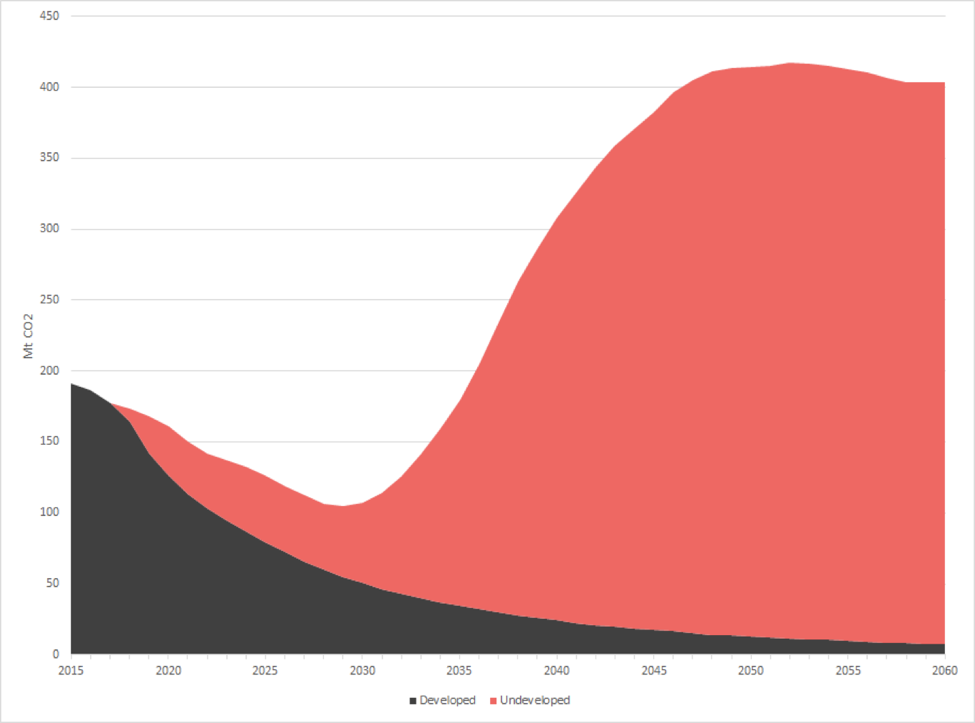

But perhaps even more alarmingly, the project will be a climate nightmare. Large-scale shale development in Argentina would push the country far off of a trajectory to reduce emissions to near zero by mid-century, in line with a scenario where global warming is held below 2 degrees C. If development of Vaca Muerta and other shale plays proceeds, emissions from Argentine oil and gas production are projected to rapidly increase, doubling by 2050 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Projected Emissions from Argentine Developed and Undeveloped Oil and Gas Production, 2015-2060

Source: Rystad Energy UCube, October 2017 (production data); IPCC (emissions factors)

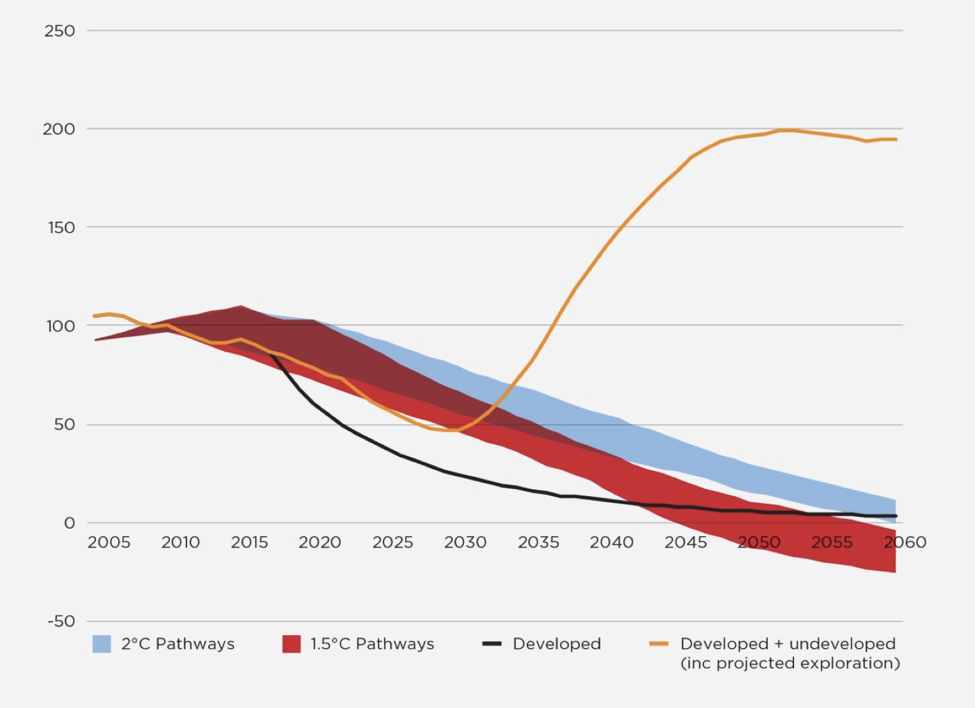

The projected production is enough to propel the country’s emissions trajectory far past any climate-safe scenario, and far out of line with a Paris-compliant pathway (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Rates of Change in Emissions from Argentinian Oil & Gas Fields Relative to a Global Paris-compliant Emissions Trajectory*

*Base year 2010 = 100%

Source: Joeri Rogelj et al.[2]; Rystad Energy UCube, October 2017

If Argentina instead focuses on planning for a managed decline of already producing fields, emissions from the country’s oil and gas sector could fall largely in line with the rate of reductions needed to keep warming below 2 degrees Celsius.

G20 governments – or at least the G19, without the United States – have an opportunity to truly commit themselves to a clean energy future, and to support Argentina on a course for managed decline, but it will mean ending the narrative of natural gas as a bridge fuel. Locking in this production now will drown out renewable energy sources that are already cost competitive and must be scaled up to address the climate crisis.

[1] The G20 countries include: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States and the European Union.

[2] Emissions pathways are adapted from Joeri Rogelj et al., “Energy system transformations for limiting end-of-century warming to below 1.5°C,” Nature Climate Change, Vol.5, June 2015, p. 520. The study shows a range of scenarios for emissions pathways that would lead to achieving the likely chance of 2°C or medium chance of 1.5°C outcomes.

What can we do to persuade these countries in the G20 to focus on renewable clear energy and not develop the methane gas in their countries? It’s challenging enough to curtail the use of developed gas reserves.