Every year today is the one day that I dread. Even now twenty years on, today does not feel like any other day. It is not a normal day.

Every year today is the one day that I dread. Even now twenty years on, today does not feel like any other day. It is not a normal day.

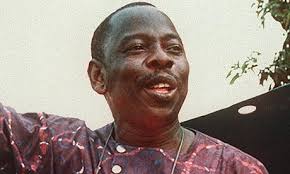

It was twenty years ago today that the world watched in horror when the Nigerian junta murdered the writer and activist, Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni.

Their crime you may well ask? To campaign against what Ken called Shell’s “ecological genocide”; the company’s chronic routine air pollution; oil spillages, its collusion with the military and its blatant double standards of operation.

I had been working with Ken and others to document Shell’s appalling environmental and cultural legacy. When someone you know is murdered in such unjust and appalling circumstances, the scars run all the deeper.

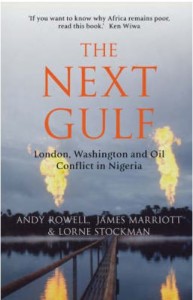

I recorded some of the pain of that day in the book, The Next Gulf, which I co-authored with James Marriott and Lorne Stockman: “It is said that those who are old enough knew where they were when Armstrong landed on the moon, when Kennedy was shot, when Lennon was murdered, and we all remember where we were on September 11th 2011. I and others will never forget 10th November 1995, and the dreadful feeling that the international community had let Ken down. I still believe we failed him in his darkest hour”.

I recorded some of the pain of that day in the book, The Next Gulf, which I co-authored with James Marriott and Lorne Stockman: “It is said that those who are old enough knew where they were when Armstrong landed on the moon, when Kennedy was shot, when Lennon was murdered, and we all remember where we were on September 11th 2011. I and others will never forget 10th November 1995, and the dreadful feeling that the international community had let Ken down. I still believe we failed him in his darkest hour”.

I am not alone in feeling outrage at Ken’s death. This morning, the wonderful arts / environmental group, Platform held a vigil outside Shell’s headquarters in London. The event included readings, poetry, art inspired by the Ogoni struggle and Ken. Tonight Platform is organising a “Dance the Guns to Silence” event in London too. If you live in or near London, get there.

There of course will also be events in the Niger Delta today too. But one important one will be missing. Ten years ago, as part of its Remember Saro-Wiwa campaign, Platform commissioned a commemorative bus, by the artist Sokari Douglas Camp. It had a sentence from Ken carved into the side: “I accuse the oil companies of practicing genocide against the Ogoni.”

Although the bus was commissioned in London it had never been to Nigeria. So for the 20th Anniversary of Ken’s death it was shipped by Platform to the country.

For the last eight weeks, the bus has been impounded at Lagos port by Nigerian Customs who are refusing to release the bus. Ironically the head of Nigeria Customs Service is Colonel Hamid Ali who was a member of the tribunal that condemned Ken and the other Ogoni to execution back in 1995.

The impounding of the bus has caused outrage amongst artists and activists both in the UK and Nigeria. AkpoBari Celestine Nkabari, National coordinator for Ogoni Solidarity Forum-Nigeria argues: “We have a right to mark the anniversary of the killing of Ken Saro Wiwa. We have a right to erect a remembrance for the many dead and for the suffering we have been forced to exist in. The Bus belongs to the Ogoni people and it is illegal for the Nigerian authorities to seize it for no reason.”

Sokari Douglas Camp, the artist who created the sculpture, has called for the bus to be released “so that this gift from allies in the UK can create a space to reimagine the future of Nigeria. This is a call for freedom of expression to both honour the people who have fought for justice in Ogoniland and the people struggling for justice today.”

And that is the problem. Twenty years on, everything has changed, but nothing has changed. For example, just think back to when Ken died: the internet was in its infancy and mobile phones were a preserve of the rich. Now we live in a internet, connected age.

So much has changed, and yet for the people of the Delta nothing has changed. The majority still live in poverty. Ogoni still is highly polluted. The communities are desperate for a change that never comes.

Indeed, four years after the publication of a ground-breaking and highly damning report by the UN Environment Programme on oil pollution in Ogoniland, the report’s recommendations – that Shell clean up its mess – have still not been implemented.

The UNEP report recommended that US$1 billion be allocated for the clean up. In the 4 years since the report was published Shell and the Nigerian government has failed to implement its recommendations.

To mark the occasion, Environmental Rights Action/Friends of the Earth Nigeria (ERA/FoEN) have asked the Nigerian government to compel Shell to act to clean up the pollution. But the chances of that happening remain slim.

“Shell and the other companies, as well as the Nigerian government should immediately implement the recommendations. Shell should also compensate communities affected by continuing oil spills and agree to pay their share of the full cost of cleaning Ogoniland and other affected areas of the Niger Delta, ” said Godwin Uyi Ojo, executive director of ERA/FoEN.

Despite twenty years passing, the Nigerian elite still cannot hold multinationals to account and put the poor impoverished communities of the Delta first.

As Ken’s son Ken Wiwa writes in today’s Guardian: although the military junta is long gone, “Nigeria’s civilian government has yet to come to terms with a man and a community whose story stands as enduring testimony to the consequences of reckless and unaccountable oil production.”

Wiwa adds: “If my father were alive today he would be dismayed that Ogoniland still looks like the devastated region that spurred him to action.”

And that is why the Nigerian elite still fear Ken’s legacy. The great African elephant still fears the mouse. And the reason: Because they stand impotent, unable to enact change, unable to force Shell to clean up Ogoni and provide basic sanitation, housing, water and education for the Ogoni and other communities in Nigeria. They continue to fail their people, and allow companies like Shell to shun their responsibilities.

And that is why the Nigerian elite still fear Ken’s legacy. The great African elephant still fears the mouse. And the reason: Because they stand impotent, unable to enact change, unable to force Shell to clean up Ogoni and provide basic sanitation, housing, water and education for the Ogoni and other communities in Nigeria. They continue to fail their people, and allow companies like Shell to shun their responsibilities.

If Ogoni was in Holland or the UK, Shell executives would be behind bars for crimes against the environment and probably much else. But to this day they walk free as the air we breathe.

Until radical and lasting change comes to the communities of the Delta, including a widespread clean up and compensation programme, and until the communities receive a just amount of money for the oil drilled from under their land, the mighty elite will still fear a man who has now been dead twenty years. Because everytime they see his picture, they know they have failed their people.

We may be winning the battle against the oil industry elsewhere, but as Ken said twenty years ago, in Nigeria, the struggle continues. But as Platform rightly points out: “They can hold the bus, but they can’t stop the movement.”