This morning in Vienna, Iran finally reached a deal on its nuclear programme with the P5+1, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany. The deal is big news for energy markets.

This morning in Vienna, Iran finally reached a deal on its nuclear programme with the P5+1, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany. The deal is big news for energy markets.

Iran holds 9% of the world’s oil reserves and 18% of its natural gas, but its production has been held back by international sanctions. The lifting of those sanctions in the coming months will put more downward pressure on prices. More fundamentally, it could transform the energy landscape, and bring to a head the contradiction between governments’ concern about climate change while expanding fossil fuel extraction.

When will sanctions be lifted?

The sanctions won’t be lifted immediately. After the UN Security Council endorses the deal – likely in the coming days – the clock will start towards ‘Adoption Day’, a maximum of 90 days later. Iran will then implement suspension of agreed nuclear activities, while the EU and USA will pass regulations to end sanctions. Those will come into effect on ‘Implementation Day’, when the IAEA verifies that Iran has complied with the restrictions. (The detailed schedule is in Annex V of today’s agreement).

Only at that point will Iran start to seriously invest in increasing its oil and gas production, which can take months to have effect. Energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie estimates Iranian production could increase by 600,000 barrels per day (bpd) by end of 2017, from the current 2.7 million bpd to 3.3 million.

Still, both the post-sanctions release of Iran’s stockpiled stores of extracted oil, and the anticipation of greater future supplies, will push down the oil price.

Transforming the energy market

Barring other disruptions, a sustained period of low prices will further hit the economic viability of high-cost ventures such as the Arctic and the tar sands. On the face of it, this sounds like good news for the climate.

The problem is what happens next to oil markets, as the emphasis shifts from expensive to cheap resources such as Iran’s. Expansion of low-cost oil production is likely to be self-reinforcing, as governments encourage higher production rates, in an attempt to offset falls in revenue.

Higher production means lower prices, means higher demand. According to the International Energy Agency, global oil demand in the first quarter of 2015 was 1.7 million bpd higher than a year earlier, driven especially by U.S. gasoline demand.

Big Oil on the prowl

Oil majors are well aware of the strategic implications of a potential shift to low-cost oil production. They will be on a charm offensive in the coming months, as they position themselves for potential production contracts in Iran, which could happen in 2016 or 2017.

A Shell team visited Tehran last month. While Shell is leading the oil pack in the financially and environmentally reckless move to drill in the Arctic, the company is also hedging its strategy by being ahead of most in lining up for a piece of Iran. Company officials also met the Iranian Oil Minister in the run-up to the OPEC meeting in Vienna.

Shell’s Chief Executive Ben van Beurden has said his company will be interested in Iranian oil “the moment the sanctions regime has changed”.

So far, the Iranian government seems happy to oblige. It has announced that it plans to invite companies in with highly generous, 25-year contracts, which would break from the usual practice in the oil-rich Middle East (and in Iran itself) of running oil industries in-house, or on contracts that give limited powers to investors. Of course, higher profits for the companies means lower revenues for Iran.

The unfortunate echo here is of Mohammad Mossadegh, the elected Iranian prime minister who was toppled in a 1953 coup sponsored by the CIA and MI6, after he cancelled an unfair, multi-decade contract held by BP and covering most of the country. Iranians may wonder whether returning oil production to international companies is the best way to boost their oil production.

Whether investment comes from multinational companies or the Iran’s public sector, how should climate campaigners respond the prospect of increased Iranian oil production?

U.S. vs Iranian oil production

If we are to address climate change, clearly the curve of oil production needs to be heading down, not up. But we can hardly expect the onus of restraint to fall on Iranians, as they emerge from particularly brutal sanctions that have caused mass unemployment, made food unaffordable for many and deprived the sick of medicine. Equity is an issue for energy supply as well as for demand.

There are those, of course, who are unmoved by Iranian suffering, or indeed by pushing climate change well into the danger zone. Oil companies, and their supporters in Congress, have taken a trip into the absurd, trying to equate Iranian sanctions (a security policy, applied internationally) with the U.S. ban on crude oil exports (an energy policy, applied domestically).

For example Lisa Murkowski, chair of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources committee, has complained that “Any deal that lifts sanctions on Iranian oil will disadvantage American companies unless we lift the antiquated ban on our own oil exports”.

With U.S. oil production at more than three times Iran’s, and the U.S. accounting for nearly 60% of the world’s increase in oil production in the last five years, it’s clear Murkowski is just being opportunistic. Furthermore, Oil Change International’s analysis has shown how lifting the export ban would increase U.S. production, and worsen the climate problem.

Whose carbon budget?

We know that global fossil fuel reserves exceed what science tells us we can afford to burn at least threefold. That means that any further exploration for new reserves constitutes a dangerous addition to the climate time bomb. But even the existing reserves are too much, so it raises the question of which of them should stay in the ground.

Even aside from the shrill voices against the U.S. crude export ban, some institutions in industrialised countries assume that it is OPEC members’ reserves that will be left unburned.

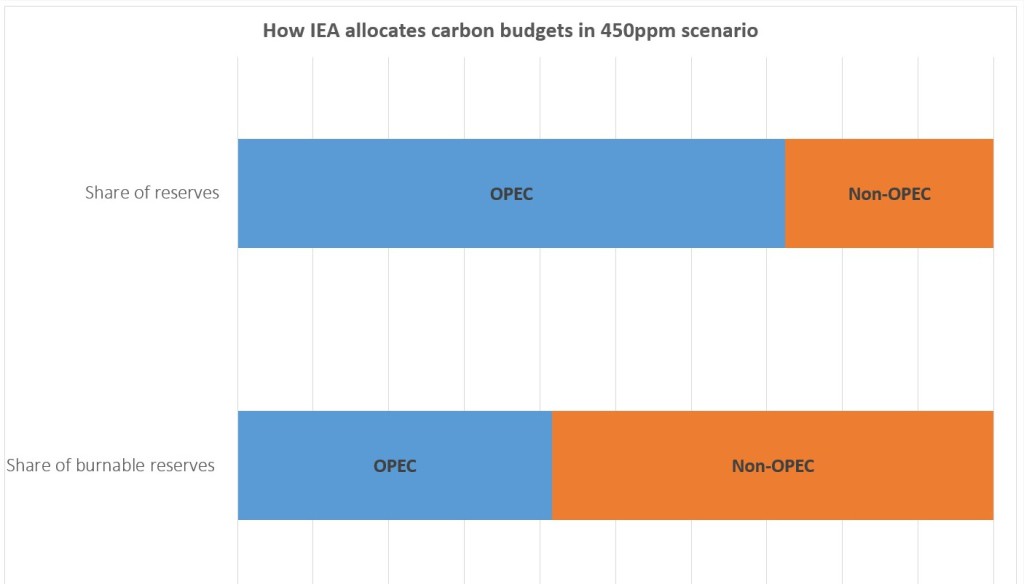

For example, the International Energy Agency suggests that although OPEC countries have 72% of the world’s oil reserves, they should have just a 42% share of what can be burned before 2035 in order to keep atmospheric CO2 concentrations below 450 parts per million (which would give a 50-50 chance of staying within 2°C). [source: IEA World Energy Investment Outlook 2014, pp.87-8]

Civil society will continue to grapple with how to share the carbon budget fairly. However, an assumption that others will make the cuts or that the cuts can come later has all too often been the cause of failure in climate politics.

One important piece of the puzzle – building on the Obama administration’s approach to the Keystone XL pipeline decision – is to demand that public institutions routinely apply a ‘climate test’ to decisions new energy developments and policies: of whether they would push the world above 2°C of warming. An inherent part of that would be transparent assumptions about how the carbon budget is shared.

The oil industry’s demand to lift the U.S. crude export ban is almost precisely the opposite of what is needed. Today’s deal in Vienna makes it all the more urgent that countries like the USA address their contribution to the dangerous excess of carbon extraction.