(This blog was written in collaboration with Jenny Banks, Climate & Energy Specialist at WWF UK)

Yesterday BP published its 2035 Outlook for Energy, the company’s view of what the future of energy might look like.

Once upon a time, oil companies liked to portray themselves as being at the cutting edge of science and technology. Today BP did the opposite, downplaying the seriousness of climate change, and dismissing fast-advancing clean energy technologies.

Organisations that remain stuck in the past tend to decline when faced with a changing world. Could this be where BP is headed?

Denying climate action

According to BP’s forecast, nothing much will change in the energy market over the next 20 years. Fossil fuels will still, BP believes, provide over 80% of the world’s energy in 2035, with emissions increasing by 25% from their current levels.

In contrast, the International Energy Agency says emissions would need to be just over half BP’s predicted level, to have even a 50-50 chance of keeping global warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels – the internationally-agreed target.

BP knows this. The company admits that “Emissions remain well above the path recommended by scientists.” Given that scientists warn that that would mean “severe, widespread, and irreversible” global impacts, BP is remarkably relaxed about this fact. And conversely BP talked down the prospects of even closing part of the gap with the IEA’s 450 Scenario, due to “considerable challenges”.

BP knows this. The company admits that “Emissions remain well above the path recommended by scientists.” Given that scientists warn that that would mean “severe, widespread, and irreversible” global impacts, BP is remarkably relaxed about this fact. And conversely BP talked down the prospects of even closing part of the gap with the IEA’s 450 Scenario, due to “considerable challenges”.

The company must also be assuming no further significant political progress on climate, including at the global summit in Paris at the end of 2015. In other words, it’s betting against the trend of increasing policy and legislation.

Technology sceptic

Perhaps even more strikingly, BP is sceptical of technological change. Its predictions mostly extrapolate the status quo, with continued dominance of the same energy sources, primarily oil, coal and gas. There is no room for disruptive technology in BP’s vision.

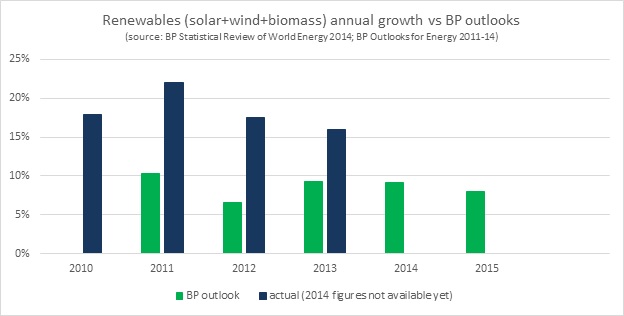

But one thing BP doesn’t extrapolate from current trends is renewable energy growth. Every year BP’s outlook, published annually since 2011, has predicted an immediate drop in renewables’ growth rate, from 15-20% per year to below 10%. Each year, renewables have grown at almost double the rate BP predicted. Rather than rethinking its assumptions, BP has now wrongly forecast a collapse in renewable growth rates, for five years running.

In fact, the difference is even wider than that, if we take out biomass from BP’s renewables figure. As a mature technology, biomass grows relatively slowly, and so its inclusion masks the rapid recent growth of wind and especially solar. According to BP’s own figures, wind and solar together grew by 27% a year over the last ten years.

In fact, the difference is even wider than that, if we take out biomass from BP’s renewables figure. As a mature technology, biomass grows relatively slowly, and so its inclusion masks the rapid recent growth of wind and especially solar. According to BP’s own figures, wind and solar together grew by 27% a year over the last ten years.

Since they are compounded, growth rates make a big difference. If wind and solar were to sustain a 25% growth rate, they would catch up with oil in just thirteen years (and account for 25% of the world’s energy production).

At some point, that growth will slow down. But there are good reasons to believe that won’t happen just yet, as solar and onshore wind become increasingly cost-competitive with fossil fuels.

The other major driver of renewable energy growth is the trend from centralised to distributed power generation. The Wall Street Journal has described this trend as creating a potential “death spiral” for coal- and gas-burning utilities.

In December, German utility company E.ON accepted the reality of this structural shift when it announced that it would split into two companies: one focused on renewable energy and distributed generation for long-term growth, and one on centralised fossil fuels for riskier investment.

Electric vehicles

As a transportation fuel, oil faces less immediate competition than coal, gas and nuclear face in power generation.

The most advanced non-oil transportation fuel is electric power. Electric vehicles (EVs) are at an earlier stage of development than renewable energy, having only been launched onto the mass market four years ago. But they too show potential for rapid acceleration, especially when combined with renewable power in home-based decentralised systems.

In last year’s edition of the outlook, BP predicted that EVs would remain uneconomical, and account for only 7% of vehicle sales in 2035. Since then, there have been several developments, including Tesla’s decision to build a battery ‘gigafactory’ in Nevada, Chevrolet’s to bring out an affordable long-range EV known as the ‘Bolt’, and several projections of falling costs.

Given improvements in battery technology, investment bank UBS projects that EVs could be cost-competitive with oil-fuelled cars by 2020, even without subsidies. Bloomberg forecasts that in the USA, EVs will constitute 6-9% of the fleet (not just new sales) as soon as 2020.

So did BP revise its prediction for EV penetration to reflect the latest developments and forecasts? No, it didn’t mention EVs at all.

Thinking about the future

Of course, none of us knows what the future holds. But BP’s view that the future will look very like the present is not a smart prediction. In reality, technological shifts often happen fast, and those who are most affected are generally the least able to see them coming.

The best way to think about the future is to consider several different scenarios, to encompass a range of possible courses of events. Earlier BP outlooks considered an alternative scenario where there was policy action on climate; now the company undermines the credibility of its forecast by looking at only one, evidently self-serving, possible future.

In the long run, BP does itself no favours by positioning itself as an organisation that does not respond to science or believe in human capacity to address major threats like climate change.

If it remains stuck in the past, and unable or unwilling to adapt to an evolving world, BP might just end up consigning itself to history.